Washington Man Facing Prison After Foraging for Wild Mushrooms

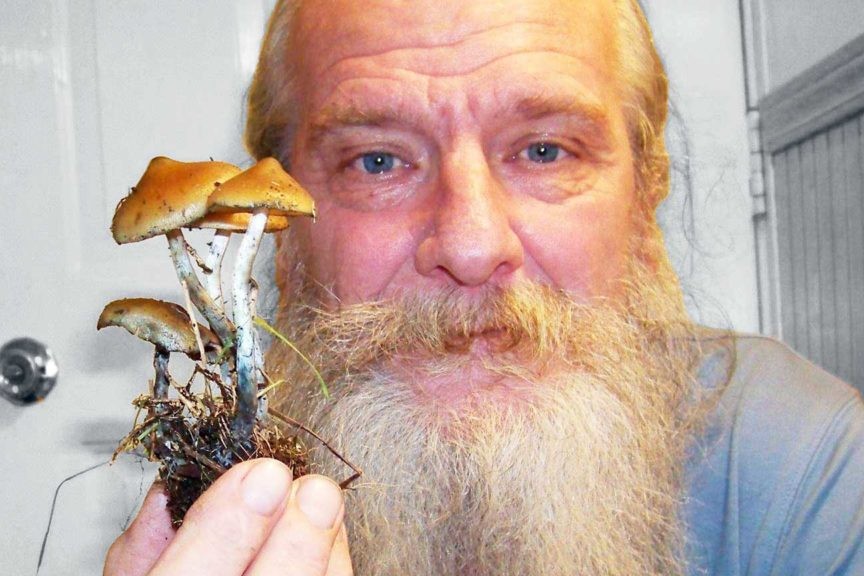

Paul Lee Corbett is facing a potential prison sentence of five years for possession of psilocybin mushrooms.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Paul Lee Corbett of Washington, 63, is a man of great adventure with a deep love for nature. Between 1968 and 1976, he lived, studied, and traveled throughout the Pacific Northwest, the Rocky Mountains, and Alaskan regions. He has spent most of his life in Alaska, where he supported himself and his family by utilizing the environment around them. He set gill nets and long lines for fish, dug clams, hunted his meat, grew vegetables, and foraged. His adventures include traveling in 16-foot skiffs on the open waters of the Pacific Ocean and trekking 1,600-mile round-trips between Alaska and British Columbia. “I loved nature and the secure peace of being in it,” he says.

While mastering his external terrains, Corbett simultaneously built a strong relationship with his internal landscape with the use of entheogenic drugs, such as cannabis, LSD, and psilocybin-containing mushrooms. Corbett knows quite a bit, in fact, about psilocybin mushrooms—and not just from eating them. He’s a skilled forager with knowledge of the many different species of psychedelic mushrooms—of which there are hundreds, belonging to about a dozen different genera.

He credits LSD in particular with having “changed [his] mind in every direction” and relieved him of his heroin addiction. But the lasting effects were even more profound. “I no longer felt comfortable in this society, the United States, or really any society,” he says. After his experiences with drugs, he left the U.S., traveling northward before arriving in Alaska, beginning his life in remote destinations.

Currently, Corbett is facing a potential prison sentence of five years for possession of psilocybin mushrooms. In November 2016, he was arrested for picking wild mushrooms at Cape Disappointment Park in Washington state. He glimpsed what he believed to be a yet unidentified species of psilocybin mushroom, picking specimens of it for later analysis. Corbett maintains his innocence, arguing he committed no crime and injured no one. He was only exercising his natural curiosity, he says.

He first picked wild psilocybin mushrooms outside Seattle in 1972. “That kinda opened my eyes to the early information about season and location, so I became curious about that,” he tells me. “Eventually I found other types of psilocybe. Once you find the mushroom, you learn about the other mushrooms that grow with it, what kind of trees there are, what kind of medium they grow in, whether it’s grass or bark. The mushrooms educate you about the rest of the forest and the environment, too.”

Corbett was hiking in Cape Disappointment Park when he spotted large red mushrooms in a wood chip pile, which were to his knowledge, unidentified. A sign posted nearby read: NO MUSHROOM PICKING: VIOLATORS SUBJECT TO CRIMINAL CITATION. Corbett ignored it, elated by his discovery. “Everyone that goes there thinks those mushrooms are Psilocybe azurescens, but they’re not. They’re more clean feeling like the ‘liberty cap’ [Psilocybe semilanceata], and a very, very beautiful mushroom.” Close by, in the grass, he spotted true azurescens. More of the mystery mushrooms grew by the spot where Corbett had parked his truck.

The odd mushrooms, Corbett believes, were a sub-species—if not an entirely different species—of azurescens. He picked 10 specimens from the woodchip pile, and put them in a plastic bag along with 10 of the classic azurescens. “I put them together because they were clearly different, with no mistake whatsoever. They don’t look anything alike.” After storing the bag in his truck, Corbett put ten more mushrooms in his pocket before he heard a cry: “Police! Hold it right there!” A park ranger darted out of the brush with a gun pointed at Corbett’s face.

The ranger felt in Corbett’s pocket for the mushrooms, then handcuffed him. Another park ranger soon arrived. Corbett calmly revealed where his other mushrooms were stored, and the officials searched his truck. He was arrested and taken to the local jail. After the police called a judge, they were advised to release Corbett on his own recognizance. He hitchhiked back to the Washington coast to find his partner, Joyce, whom he has never left alone for more than two hours due to her physical ailments.

After his arraignment, Corbett was charged with felony possession of a controlled substance, punishable in Washington by up to five years in prison and $10,000 in fines. He was offered a plea deal of one year of felony probation with 15 days in jail, but he immediately turned it down. “Joyce uses [medical] cannabis to cut down a quarter of her narcotic pain medication,” he explains, “but on probation she couldn’t even be in the same place I’m in.”

“Plus,” he adds (with a hint of annoyance), “I didn’t commit a crime. There’s no injured party involved in any of this, only Joyce and myself. In fact, over my time of picking mushrooms, I’ve probably saved a couple hundred people who were really stupid.” Not all mushroom species are equally safe for consumption, he states. Through the knowledge he has gained and shared over a lifetime of foraging, he has prevented his pupils from suffering potentially fatal side effects.

Corbett has been to court several times since the incident, but the case has not yet been settled. Twenty-four hours before one of his court dates, he was ordered to leave his wife in the hospital on risk of contempt of court—despite her doctor’s pleas to the contrary—to drive six hours from Fort Townshend, his residency, to attend his hearing.

Corbett has been frustrated by what he considers insufficient or even counterproductive advice by his lawyers, who have urged him to plead guilty. They have refused to discuss anything relating to mushrooms or entheogens, and hope Corbett will settle for the plea deal and probation. But Corbett is determined to challenge the law and prove his innocence.

He has since fired his attorneys and he hopes to hire one who will best represent him and his unique situation. He has opened a crowdfunding campaign to fund his legal expenses and his partner’s medical expenses.

Since his arrest, Corbett and Joyce have been traveling around Washington, following a recent hospitalization and surgery that Joyce underwent. He states that the worst likely consequence of his conviction would be leaving behind his frail partner. “We’re living in a camper now—which is a nice one—but she’s not capable of doing that on her own.” They are both counting on disability insurance, with no money to pay rent.

Corbett heaves a heavy sigh as he recounts his tale to me. “This has got to end. People need to be educated. My hope is to educate the whole courtroom. It’s a mystery to all of us why these things are illegal. And it’s a mystery to me why the word ‘liberty’ doesn’t apply to my curiosity and my entheogenic use.”

Corbett is uncertain about his own fate, but he hasn’t lost faith for his younger peers. “I’m hoping that education with these entheogenic substances will help us change the world, because I’m worried about it. I’m hoping this new movement now can change things. So we look at everything—each other and this whole earth—in a way that is a little more caring and a little more on the side of being a good steward.

“I don’t think people really get to know [the mushrooms] and where they live. They live in beautiful places, amazing places. And then again they also follow us around everywhere we go. They want to be with us, and they want to teach us.”

Corbett will return to trial in November 2017, after two more hearings scheduled in the fall.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.