Ibogaine presents unique challenges in how we approach harm reduction and treat addiction | Part 1

This series explores the unique challenges ibogaine presents in how we approach plant medicine, harm reduction, and treatment for addiction, through the lens of ibogaine researchers, providers, patients, and advocates from around the world. Read the full series.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

My addiction started when I was 13, with prescription medications. I knew it was over the very first time I took an opiate. It was set, that this was going to be my addiction for a long time.”

There’s a brief silence as the woman sitting across from me takes a moment to swallow the lump in her throat. Her name is Amy. She’s a nurse from Canada, and she’s spent the majority of her life addicted to opioids.

“It developed into a more serious addiction over time, to the point where I was using them intravenously, when I became a nurse and had access to injectable medications. So my use got really, really out of control.”

We’re sitting amidst a hustle and bustle of people as they come and go through the hotel lobby. The sound of excited chatter dominates the space, and despite the heavy undertones of our conversation, you can feel the electricity in the room.

This is the setting for the European Ibogaine Forum, a small conference that took place in Vienna, Austria this past September. The event attracted an unlikely crowd of people from all walks of life. Doctors, researchers, drug users, and hippies from around the world came together for their shared interest in an obscure hallucinogenic alkaloid – ibogaine.

Sourced from the African shrub Tabernanthe iboga, or simply iboga, ibogaine is reputed to have the profound ability to eliminate opioid cravings and withdrawals. And unlike other psychedelics, ibogaine can be fatal. As such, it presents unique challenges in how we approach drug policy and addiction.

Iboga has a long history of use in west-central Africa. Consumption of the root bark, specifically, is intimately tied to the ancient spiritual discipline known as Bwiti, which is believed to have originated with the Babongo people in the Southern forests of Gabon. It’s said that the Babongo shared their knowledge of iboga with a migrant Bantu tribe that settled nearby, the Mitsogho.

Bwiti continued to evolve as the Mitsogho people came into contact with other tribes, such as the Fang, and now exists in the form of many diverse and interconnected syncretic belief systems that use iboga as part of their practice. In these contexts, iboga is typically ingested during initiatory rites of passage, for healing, and to make contact with ancestors.

Iboga and its constituents remained relatively unknown in the West until recent years. Ibogaine was first isolated in 1901, and in 1939 it was marketed in France under the brand name Lambarène for the treatment of depression and fatigue. It wasn’t until 1962, on the streets of the Lower East Side in New York City, that the drug would attract any serious international attention.

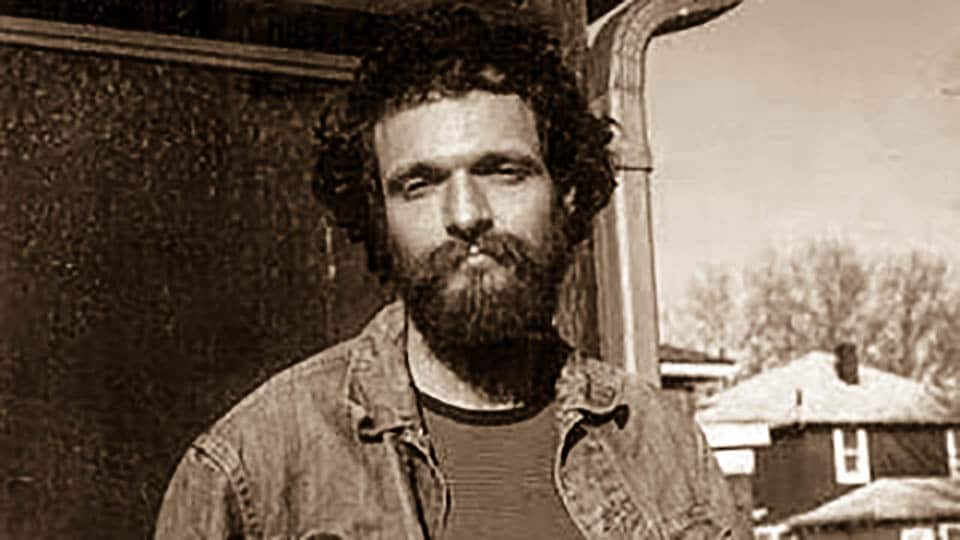

Howard Lotsof was only 19 years old when he first tried ibogaine. He was addicted to heroin and willfully experimenting with any substance he could get his hands on. The story goes that he was given ibogaine by a friend of his, who happened to be a chemist. Howard had never heard anything about the strange compound, and he chose to ingest it for no reason other than curiosity. Yet curiously enough, by the time the experience was over, he realized he no longer had any cravings for heroin whatsoever.

He went on to share the drug with his friends, who were also addicted to heroin, and it seemed to have the same miraculous effect on them. From that point on, Howard became a kind of evangelist for the addiction-interrupting potential of ibogaine. Between 1985 and 1992 he was awarded numerous patents for utilizing ibogaine as a rapid method for the interruption of various addictions, and he provided pilot data for a research program that eventually resulted in an FDA-approved Phase I clinical trial for ibogaine in the treatment of addiction.

At the same time, Lotsof also offered underground treatments and provided ibogaine for the Junkie Bond, an advocacy group for drug users. This work served as the foundation for the users-helping-users movement, a treatment modality rooted in harm reduction and self-care.

Howard died in 2010. Ultimately, his crusade involved a small army of devoted individuals, some of whom are featured in this series. Howard’s journey laid the groundwork for a movement that’s been steadily growing since his fateful experiment in 1962. Since his death there has been a tremendous resurgence of interest in psychedelics, and drug-related overdoses have continued to rise at exponential rates around the world. In fact, overdose is now the number 1 leading cause of death in Americans under 50. Given these circumstances, perhaps it’s inevitable that the ibogaine movement has grown so significantly since Lotsof’s passing.

Though still relatively obscure, the premise that ibogaine can be used for the treatment of addiction is becoming more accepted. Since 2010 there have been over 200 scientific papers about ibogaine published in academic journals, and legislation to legalize it for medical use has been introduced in states like Vermont. With all of this attention, one might wonder why it’s still so unheard of.

Ibogaine is unlike other psychedelics in that it is potentially cardiotoxic and physically dangerous. The National Institute on Drug Abuse abandoned clinical trials with the drug due to safety concerns spurred by neurotoxicity observed in rat trials (however, the doses were substantially larger than equivalent doses that would be given to humans). Ibogaine is also classified as a Schedule 1 narcotic in the United States, and thus individuals seeking to use it must either find it through the black market or travel to foreign clinics in countries where it is not strictly prohibited.

“Because of the unregulated nature of ibogaine treatments, people are playing a lottery as to what kinds of results they will get,” says Hattie Wells of the Beckley Foundation. “Ibogaine clinics range from very good to pretty dangerous, and I wouldn’t recommend people take it without experienced medical supervision and a proper post-treatment program of support in place.”

That it elicits powerful visionary experiences lasting for up to 3 days is yet another factor contributing to the lack of acceptance for ibogaine as a legitimate treatment in the medical world.

“There are examples of licensed medications that carry cardiac risks, but none which also exert long lasting ataxia and a psychedelic trip. It’s not what conventional medicine would call very useable,” Hattie explains.

Ibogaine sits at the intersections of numerous social issues, tossed between movements for drug users advocacy, drug policy reform, and psychedelic research like a political hot-potato. Nobody seems to want to touch it, and yet there seems to be no better option in sight.

Amy was one of several people I spoke with at the Ibogaine Forum who had tried conventional treatments, such as methadone maintenance and 12-step programs, with limited or no success. Desperate, she ultimately turned to ibogaine as a last resort.

This conversational series is an exploration of these stories, a comprehensive look at the use of ibogaine as a medical intervention, a religious sacrament, and a source of misinformation and controversy. Opinions about ibogaine seem to vary from one extreme to the other in virtually every context– its efficacy as a treatment for addiction, its safety, and even whether or not it should be regulated at all are contested by advocates and opposition alike.

I found Amy’s story particularly important to include because of how effectively it highlights the nuances of the ibogaine world. For example, it didn’t really work all that well for her, initially.

“I did a lot of research before going to the clinic in Mexico, but it actually was not a very positive experience,” she told me. “I left the clinic in a wheelchair. I couldn’t even walk. I was still having serious withdrawal that lasted for weeks after the ibogaine experience.”

When I first heard about ibogaine, I was given the impression that it’s a straightforward cure for drug addiction, a kind of magic pill that you take once to solve all your problems forever. Most of the information I could find online seemed to follow this same narrative. Yet quite frankly, there’s nothing straightforward about ibogaine at all.

Many advocates are cautious of how ibogaine may be integrated into a medicalized pharmaceutical framework, with access to it overseen by regulatory agencies with little accountability. Some voices have expressed concerns about the long-term sustainability of international demand for ibogaine, claiming that iboga is becoming scarce due to unsustainable overharvesting. Others believe these claims are politically and economically motivated.

Over the next month, Psymposia will be releasing a series of interviews and conversations featuring key figures in the ibogaine movement. Our goal is to explore diverse, and often conflicting, perspectives on the relevant issues. We spoke with clinical researchers and facilitators, underground providers, activists, policy workers, and of course, individuals who have taken ibogaine for medical, spiritual, and recreational purposes.

Amy did eventually get through withdrawal and her cravings disappeared, temporarily. Her exposure to ibogaine provided a valuable window of opportunity for her to begin making the changes necessary for her recovery.

“I had some serious trauma in my life prior to taking that ibogaine dose, and the experience helped me resolve that trauma in a way I hadn’t been able to with years of counseling. I walked out thinking, once my withdrawal was completely over with and I realized my cravings were gone, ‘This is pretty amazing.’”

The political stigma attached to ibogaine is so strong that I had to agree not to use Amy’s real name in anything published by Psymposia. Amy could lose her job and see the end of her career as a nurse if her employers were to learn that she had ever used ibogaine, despite the fact that it’s a legally prescribed medication in her country.

Like ibogaine itself, there’s much more to Amy’s story than what’s presented here. As we dive into the complexities of the ibogaine world, we’ll revisit Amy on her path to recovery. For now, we’ll start by taking a look at the cultures that have used iboga the longest. Our exploration begins in the heart of the equatorial rainforests of west-central Africa, specifically, in Gabon.

As the series evolves, Psymposia hopes to pose challenging questions that encourage us to evaluate the dominant models of addiction treatment in the United States and abroad, our engagement with plant medicines as Westerners, and the very foundations of the regulatory model that determines what is ‘medicine’ and what is not.

Read Part 2: Taking Iboga with the People of Gabon

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Jordan May

Jordan May is a writer who explores the intersections between drug policy, psychedelics, and community engagement.