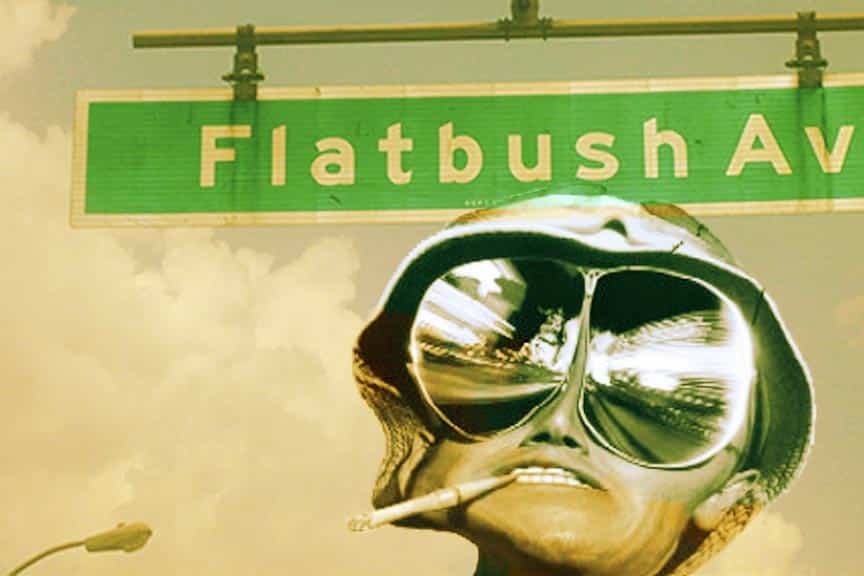

Fear and Loathing on Flatbush Avenue

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas can tell us a lot about the building of the system we are now finding ourselves stuck inside.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

The fourth LSD trip I ever took was a week after the third. After that third trip, my brain was swimming in its own imagination. I felt indestructible and there was a rush in my subconscious to maintain the feeling of being a social amoeba, to float through space and time. Coincidence and opportunity opened the door, which made the decision to trip so suddenly, again, an easy one to make.

Around hour five, after laying around in Prospect Park painting with watercolors and falling in love with the color green, my partner Ben and I walked along Flatbush Avenue; the ultimate goal was to find a bathroom. Each one we passed on our way toward Grand Army Plaza had a line. I couldn’t stand with people and explain myself, pretending to be sober. “I’d rather just hold it and keep going,” I said. We made it out to the traffic circling the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Arch.

It’s sobering to emerge from the park into a concrete jungle and a complicated traffic pattern. We walked right through it to sit in front of the fountains and rest. “I can’t think and walk at the same time,” I remember saying. Then something like, “Hey, let’s go to Sharlene’s.”

“I could drink for HOURS,” Ben said. Thirst had set in.

Once we arrive, I tell Ben to get me a Diet Coke and I head to the ladies’ room. The stall is full of graffiti: “Pussy Grabs Back,” “Women Unite!” and coincidentally or not, Greg Allman lyrics, who died the day before. I get lost in the wall, interacting with something someone else created two inches from my face. I pee for what feels like a full sixty seconds, rest my arms on the walls and they feel as if they’re stretching up the stall. My lower half relaxes.

When I reach Ben at the bar he looks over at me, his pupils the size of dinner plates. The bartender smiles at us. We’ve become regulars.

There are a few groups of people, a line of older white men—bar flies—sitting at the first ten seats next to the door. The barstools swivel and I sit with my feet on the poles under Ben’s seat, holding onto my own stool so as not to fall. I take a sip of soda and it bubbles down my throat. I look down at the floor and it slants. A hill I didn’t notice before. “Is that floor slanted?” I ask. Ben looks down at it and says, “Maybe.”

My memory flashes to the scene in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas when Raoul Duke and Dr. Gonzo arrive in Vegas and Raoul’s head is full of Sunshine Acid. The hotel bar and press check-in morphs into a reptile fest and Johnny Depp, playing Raoul Duke, calls out for golf shoes. A black tar creeps on the floor under him. I look down at my own sneakers and lean towards the slant to get a closer look.

I’ve been waiting my whole life for any semblance of the drug experiences I’ve read or learned about to happen to me—it’s what this hippie nerd dreams of. I’ve always wanted to see it, too.

I can still look down and see that floor slant. It’s a khaki-colored and black-checkered floor, like an old Manhattan bathroom tile or a mid-century diner. As far as flashbacks go, I still see the slope, knowing I couldn’t walk on it. Even as we got up to leave another beer later, I said to Ben, “Wow, that floor is definitely not slanted.”

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is my entry point for culture, phrases, and ideas about drugs, and what your brain can really do if you let it run wild. My draw toward Hunter S. Thompson is that he associated being high on ether with “some early Irish novel.” It’s the marriage of intellectualism and a silly imagination, and my favorite vocabulary of any writer.

New York City is rarely a place associated with psychedelic drugs. Our trip was at the beginning of summer when the city was just starting to get hot and the smell of rotten garbage can smack you in the face at any moment. Still, the grime and cluster of New York is comforting to me. If there isn’t a sea of people, someone yelling at me and piss in the air, it’s not really home.

The benefits of living in New York City greatly outweigh the indecency of watching the girl next to you on the subway step in gum and get it stuck in the fringe of her sandal, or watching a man mop up his dog’s drool with the sole of his sneaker on the downtown 6 Train. We call it The Greatest City In The World for a reason and we turn the other cheek when it manages to spit us out.

I’d rather be spit out on LSD into the grit of the sagging curbs of Brooklyn where the subway bulbs can tell me I’m home rather than let my ears bleed from the silence of the country.

Mimesis is an ancient philosophy, a connection between art and literature—and, as it turns out, my life. I’ve been looking for it all along. It answers the questions I didn’t even know I was asking. Have I been trying to recreate the experiences of my drug heroes, in the hopes of acquiring some kind of liberation or knowledge? Have I been living a philosophy I’ve been unaware of? Is mimesis the greatest vocabulary word I didn’t even know I was looking for? Is my great trip my life up until this moment? Is it my savage journey into the heart of the American Dream?

The baby boomers have come to fully lead this country one millionaire and billionaire at a time. While social change has occurred, not much else has progressed, and money can buy the presidency no matter who you are or what you believe.

My generation of millennials is just beginning to understand that the American Dream was never for us. It was our parents’. And now that they obtained a version they approve of, we are left with a lifetime of debt, a crippled, deregulated economy and a lack of social justice so strong it will make you want to fill your head with acid so that—for small bursts of time—the straight world is just a bit easier.

The darkness we face as a nation and the embarrassment we are to the globe is something Thompson never saw. It cannot hold; the bubble has burst and I’ll have to deal with the leftovers in my thirties, forties, fifties, and beyond.

What I found at the end of that fourth LSD trip, after watching the floor slant and straighten out, was the lesson of Thompson’s life (and Jerry Garcia’s, Ken Kesey’s, Timothy Leary’s, and many other drug heroes’).

The lesson of my trip and the lesson of Fear and Loathing became clear to me: Acid Culture is fun and games while you’re high, but you need to tend the light at the end of the tunnel. You must get up and go to work the next day, I must sit behind the keyboard and write once the circus in my brain leaves town, and the responsibility of the straight world—while daunting—will never go away. In order to escape, to trip, you must be able to play by the rules. Or else there are no rules to break. Pretending like they don’t exist will only bring destruction and addiction. The loss of so many brilliant people to drugs and basic drug hero history taught me this.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas can tell us a lot about the building of the system we are now finding ourselves stuck inside. While changes have brought some improvement, many things have stayed the same. The reptiles will stop their orgy to turn their heads to you, who is screaming. Even if you are just another freak in the freak kingdom, the cops will pull you over and you will have to make deadline. The LSD will wear off eventually and history shows it’s better to be prepared than high.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Sarah Paolantonio

Sarah holds an MFA in Nonfiction Writing from Sarah Lawrence College. She is working on her first book and lives in New York City.