This is part one of a six part series on the intersection of psychedelics and capitalism, and the early investors making it happen.

As I shuffle through Times Square, I’m tickled by a giant LED billboard displaying an advertisement for the meditation and relaxation app, Calm. It is sandwiched between three other flashing billboards—one for the TV station, ABC; another for the show, Sisters, and; one giant American flag. It seems like the antithesis of where you would expect to find a humble meditation app: in the beating heart of capitalist America, practically screaming, “I have $5,000 to $25,000 to throw around for a three-day ad slot in New York!”

And, they do.

Last year, Calm raised $88 million from investors and was valued at $1 billion. This is “fine.” Except, raising that type of money means that Calm expects to be able to pay out significant financial returns on those investments. And, when a relaxation and meditation app has to start pleasing investors, it has to start extracting value from its users.

Doesn’t that just start to feel weird the longer you sit with it? Calm claims to be making the “world happier and healthier” by teaching people how to meditate, relax, and go within. Yet, it has financial incentives to get its users to rely on and pay for Calm subscriptions. In fact, Calm made $150M from “well over” one-million paying subscribers in 2018.

To its credit, some of Calm’s content is free when you download the app. But, for anything exclusive, you must either pay $69.99 a year or $399.99 for a lifetime subscription. I know a lot of people who use this app and really like it, and I would never criticize anyone who is pursuing a healthier mental state—preferably for their own personal satisfaction, not as self-funded mental optimization for their workplace. Though, Calm likes to push that workplace optimization angle in many a blog post, citing the American Institute of Stress’ estimations that stress costs companies over $300B annually, and offering a “Black Mirror”-esque way to de-stress employees to help recoup that money.

The bottom line is that there are wealthy people who have a stake in convincing us that we need to pay for the kind of mental fitness that apps like Calm offer, and that it benefits us to give away our mental health data to an app.

Two of those wealthy people are Calm’s co-founders—Alex Tew and Michael Acton Smith—who were early investors in the next booming mental health money-maker: psychedelics. In 2018, both of them invested in ATAI Life Sciences. The company’s mission is to fund research into the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs. ATAI is the largest minority share investor in COMPASS Pathways, a mental health company currently focused on producing and administering psilocybin.

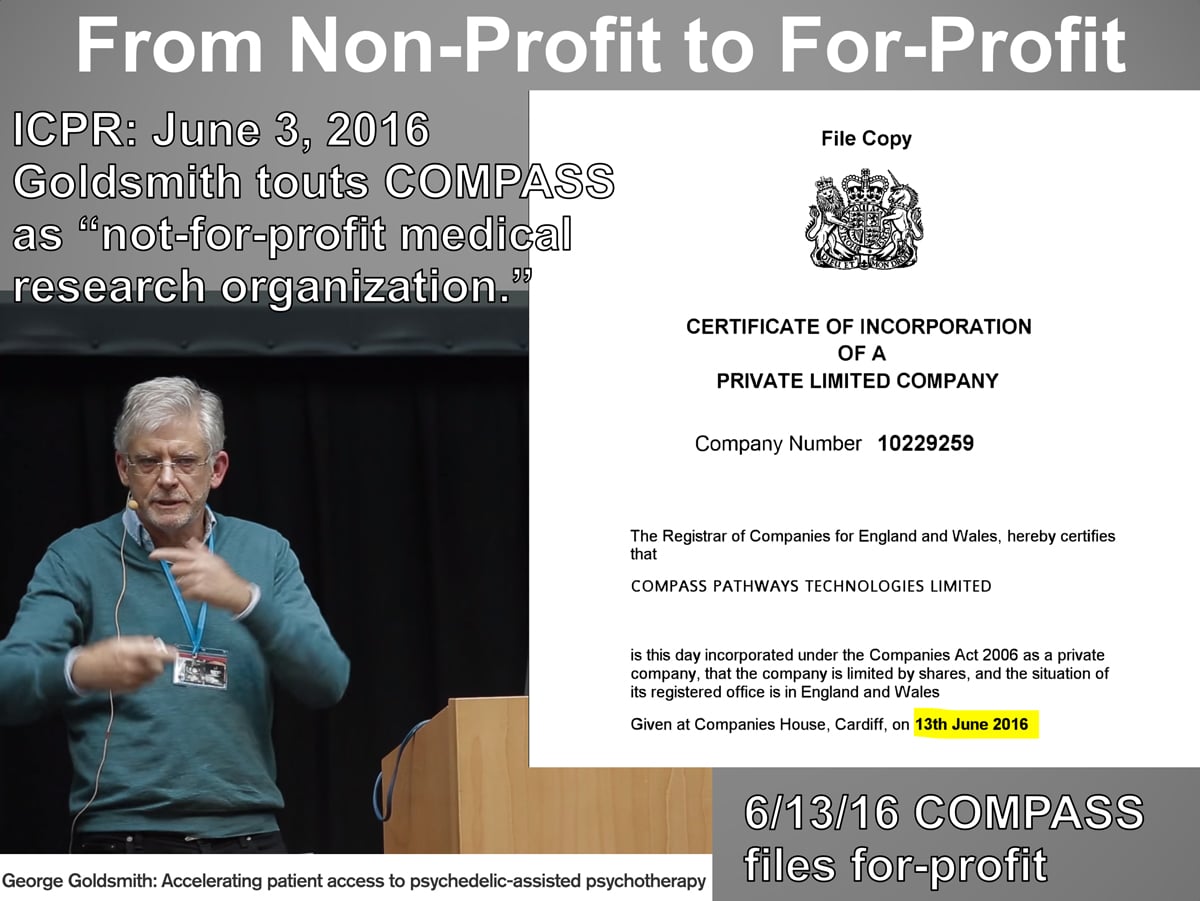

COMPASS Pathways came onto the scene hot, angering folks when they unexpectedly switched from a nonprofit, soliciting advice from well-meaning researchers, to a for-profit company backed by the likes of tech billionaire Peter Thiel. Before the switch, at the 2016 Interdisciplinary Conference for Psychedelic Research, COMPASS Pathways’ co-founder George Goldsmith said he believes that open science, sharing data, and strong partnerships are the key to success for the psychedelic community.

“We owe this to patients and we owe this to each other to look at how to do this,” Goldsmith said. “We formed a not-for-profit medical research organization to help out with some of these items.”

Goldsmith made this statement ten days before COMPASS was incorporated as a for-profit company, which went on to patent its methods for synthesizing psilocybin. You can see why people were surprised.

COMPASS Pathways’ co-founder, Ekaterina Malievskaia, claims that the reason for the sudden switch was to gain tax credits from the United Kingdom’s government; credits that weren’t available to nonprofits. COMPASS Pathways’ Chief Communications Officer, Tracy Cheung, also told me it was because they saw the for-profit model as the best way to scale. And, according to notes from a 2017 Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) board meeting, Goldsmith indicated that COMPASS Pathways, “consulted and decided the market would support a for-profit.”

Regardless of the various stated reasons, there are significant functional differences in how nonprofit and for-profit companies are able to conduct business. The notion that a company can claim its switch from nonprofit to for-profit was simply to obtain some tax credits—ignoring all of those functional differences—while publicly affirming itself as a nonprofit as it prepares to make that switch is misleading, at the absolute least.

Anyway—Calm.

Calm is one of COMPASS Pathways’ corporate partners, and the company’s therapists get access to Calm for “meditation content and training.” Calm networks well, apparently, as evidenced by their big blue billboard in Times Square. And, the whole reason my mind spun down this hole about Calm, in the first place, is because I had attended a networking event for investors in psychedelic medicine earlier that afternoon.

The 2020 Green Market Summit on the Economics of Psychedelic Investing was held in a WeWork ballroom in Manhattan on January 24. One of the presenters mentioned that a large portion of his investors were high net worth individuals from the tech industry—like the Calm guys. That’s why this billboard sent my head spinning.

Will we see ads for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in Times Square one day? Are ketamine clinics going to offer subscription services? Will my future therapist treat me with content provided by a tech start-up? Could my psilocybin provider track my mental health through a smartphone app?

Well, another of COMPASS Pathways’ corporate partners, Mindstrong Health, is developing an app it claims can track your “digital biomarkers” through your smartphone habits and alert your healthcare provider if they detect any mental health issues.

“[COMPASS] is working with people who have been at the forefront of wearable technologies,” said Rick Doblin—the executive director of MAPS—at the 2018 “Cultural and Political Perspectives on Psychedelic Science” symposium.

“So, what they’re trying to do, I understand, is make it possible to reduce the cost of the treatment. To use as much technology as possible. To have all these reminders of your depression, or your mood tracking. I don’t know what they’re talking about,” he said. “But, maybe they can end up developing some sort of a therapy that’s linked with all of this wearable technology that’s never been invented before.”

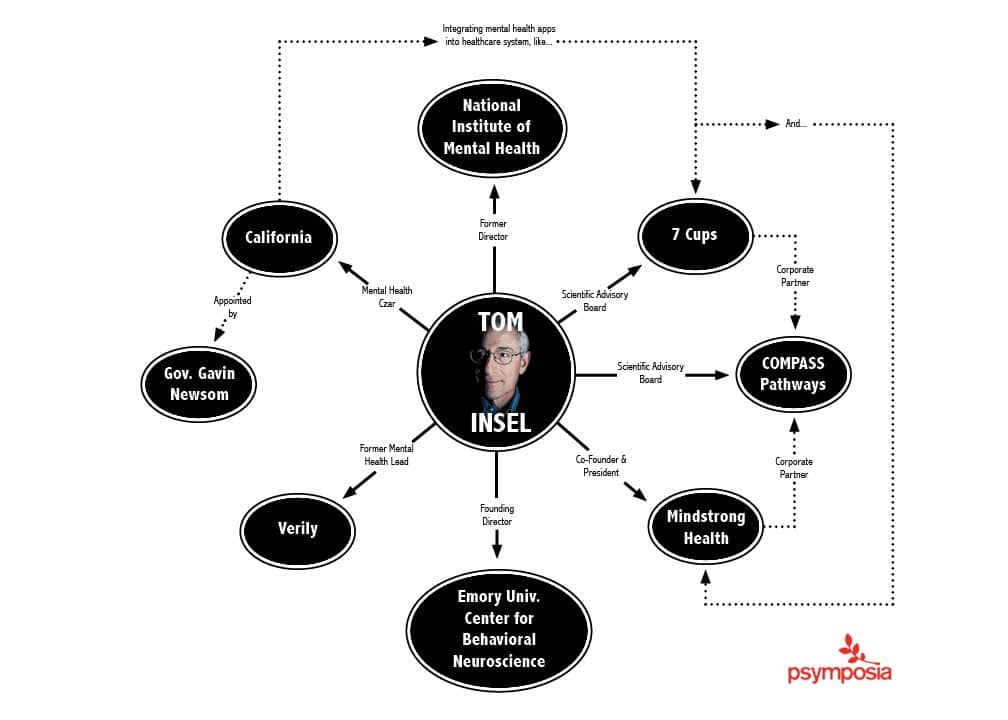

Besides the Calm founders—who conveniently invested in a COMPASS-affiliated entity and ended up as one of their corporate partners—another big player in this leap to “digital mental healthcare” is former director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and COMPASS Pathways Scientific Advisory Board member, Tom Insel.

After leaving his position with the NIMH—where he scrapped institutional support for the DSM-V, while claiming “mental disorders are biological disorders involving brain circuits that implicate specific domains of cognition, emotion, or behavior”—Insel became a lead for Google’s life sciences arm, Verily. There he focused on, “the connections between people that Google can track, analyze, and organize…to better understand and treat mental illness,” according to the Atlantic. He left Verily in 2017 to co-found the start-up Mindstrong Health, which, as mentioned earlier, tracks smartphone data (from microphones, accelerometers, GPS units, and keyboards) for mental health indicators.

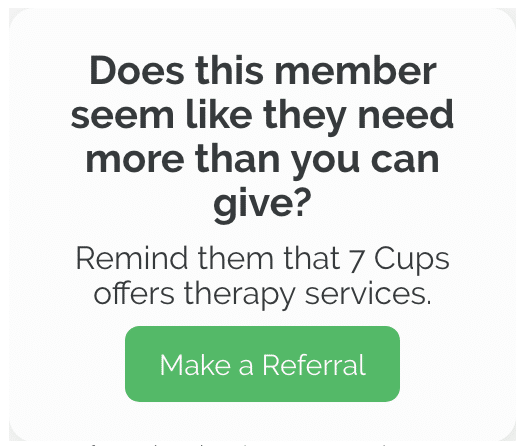

Insel hypes another of COMPASS’ corporate partners, too—7 Cups—which is a company his daughter worked for and for which he is a scientific advisory board chair. 7 Cups is an online, anonymous, text-based peer counseling and support website for people with depression and anxiety. It’s like a text-based, mental-health-focused Chatroulette, but with less dicks.

“Maybe we need to think about, if we want to bend the curve, are there things that we can do that get to that 60% of people that never [seek mental health treatment the traditional way]?” Insel asked while speaking about 7 Cups at the NatCon 2017 behavioral health conference. “Should we be re-thinking the entire premise of needing more bricks and mortar, more people, more money, and coming up with a way that meets people where they want to be? Because, all of these people are online. They’re all engaged in something, and they’re all looking for help. Sometimes they find it. Most of the time they don’t.”

His answer to the issue is companies offering online peer support like 7 Cups. With 7 Cups, you can text with a “Listener” for free, if you are experiencing anything from general anxiety, to drug abuse issues, to bipolar disorder. All it takes to become a “Listener” is a test which can be completed in 15 to 30 minutes, the requirement that you check a box confirming “I am not homicidal, suicidal, or abusing anyone,” and complete a non-verified age input requiring you to be 18 years or older (or 15 years or older, with a parent’s consent).

I became a “Listener” for 7 Cups by taking a test which goes over things like, “How to Reflect,” and, “How Open-Ended Questions Work,” just to see how easy it was to get “credentialed.” And my conclusion, after passing without even reading the materials provided, is that pretty much anybody can become a “Listener” if you have about 30 minutes to spare. This is the service that is available to anyone for free—talking with me, a stranger with no mental health training whatsoever. Though, as a “Listener,” if I am approached with an issue that seems beyond my scope, I am encouraged to let the person I am texting with know that 7 Cups does offer professional online therapy sessions. For $150 a month.

Apps like 7 Cups are being heralded as the new way to expand mental healthcare access to those who might be of lower income or who wouldn’t access therapy in traditional ways. What isn’t explicitly stated is that the financially accessible side of 7 Cups is not professional. And, digital access to professional care costs about as much as someone would spend on a monthly therapy session in person. Plus, while online therapy has the potential to give new people access to mental healthcare, critics have raised potential issues including lack of body language and expression; encryption and privacy concerns; identity fraud on both the part of the therapist and the patient; technological failure protocols; and therapist licensing issues.

It remains unclear how COMPASS Pathways and 7 Cups will utilize this technology in the future. Maybe for digital intake or integration? In the context of a for-profit system, there is a need to cut costs to remain competitive. Could expensive mental healthcare professionals be substituted for digital “equivalents?” If you think that psychedelic integration should be done through an app, raise your hand. Currently, though, COMPASS therapists are using a 7-Cups-designed “training bot” which helps them “develop and practise their active listening skills.”

The plot thickened in May of 2019, when Insel was appointed by California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, as the state’s “mental health czar.” Although this appointment is a volunteer position, according to Newsom, it still appears that Insel could have something to gain.

When asked by California Healthline in 2019 if he thought technology would play a role in improving mental health in California, Insel quipped that, “As much as one might hope there’d be an app for that—it’s really complicated.” He claimed that in his time working on a mental health plan for California, technology has barely come into the conversation. He added, “Having said that, I do think in the future using digital tools to connect people to care will be transformative.” What he didn’t say is that about 15 counties in California have geared up to spend nearly $60 million between 2018 and 2022 to integrate technology from app companies like Mindstrong into their health care system, according to STAT.

Not only that, but California is on the forefront of efforts to decriminalize psychedelic drugs, and Insel has the ear of many of the politicians involved in making that happen. Let’s not forget that Insel is on the scientific advisory board of for-profit psilocybin company COMPASS Pathways, and is partnered with them through Mindstrong and 7 Cups. It remains to be seen if potential conflicts of interest will arise if psychedelic decriminalization efforts reduce the demand for pharmaceutical psilocybin being developed and produced by COMPASS Pathways.

“We are concerned about any efforts that benefit from creation of scarcity, and we are particularly concerned about efforts that have strong connections and high resources which benefit from creation of scarcity. Our approach is to counter this with strong grass-roots advertising and encourage others to take up the mantle of pushing for abundance in whatever capacity they may have, even if this is shining light on information,” said Larry Norris, a co-founder and board member of Decriminalize Nature Oakland—a grass-roots group which led the effort to decriminalize Schedule 1 entheogenic plants and fungi in Oakland, California.

I reached out to Insel through Mindstrong and have not received a response as of the time this was published. Nor have I heard back from my request for comment from consumer protection organization Our Health California, or Decriminalize California about whether or not they see a potential conflict of interest, here.

As Silicon Valley and Big Pharma begin to work closer and closer with one another to address mental health issues, we have to ask ourselves some hard questions. Sure, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy shows promise in treating mental health. But, do we want for-profit psychedelic pharmaceutical companies—backed by some of the biggest players in mass surveillance online and in the streets—to stake their paychecks on monitoring and quantifying our digital lives?

In a world where you don’t own your personal online data—where corporations and political operatives like Cambridge Analytica co-founder Steve Bannon, (along with Robert Mercer, whose daughter Rebekah Mercer donated $1M to MAPS), can steal data from 87 million Facebook users and legally purchase the geolocation data of church-goers’ to market “Get Out To Vote” advertisements to them—are you comfortable with relinquishing your biomedical data to corporations looking to market mental health services to you?

Are you comfortable having access to psychedelic psychotherapy predicated on the requirement that you surrender your “biomedical data” to meditation or therapy apps through your phone? And, do we want the people in charge of reworking our mental health system to be those who have the largest financial stakes in “disrupting” the currently available models of treatment?

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Russell Hausfeld

Russell Hausfeld is an investigative journalist and illustrator living in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism and Religious Studies from the University of Cincinnati. His work with Psymposia has been cited in Vice, The Nation, Frontiers in Psychology, New York Magazine’s “Cover Story: Power Trip” podcast, the Daily Beast, the Outlaw Report, Harm Reduction Journal, and more.