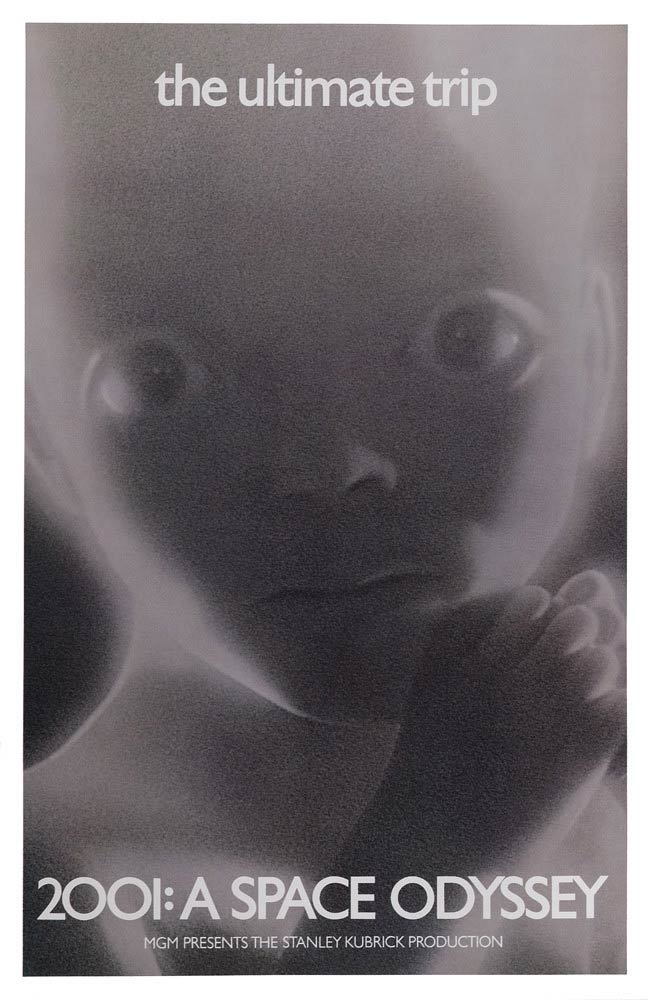

2001: A Psychedelic Odyssey

One tagline for the movie was “the ultimate trip,” so clearly Kubrick, or at least the film’s marketing team, were very aware of the psychedelic implications of the film.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Idid not know that I was in for the most profound psychedelic experience of my life as I sat down for a 70-mm screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey on the Fourth of July.

But with the guidance of Timothy Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience still ringing in my ears from the day before, and the chemical assistance of a sativa edible, I would soon find myself in a state beyond language, watching in film form a process of rebirth that I myself felt sitting in the audience.

The setting was ideal: Chicago’s Music Box Theater, where the main theater is lit with sparkling starlight and projected clouds idly drifting across the ceiling.

As the film began, I soon sensed the clear possibility of falling completely into the film. Rapt in concentration, the film’s strong thematic concern with the divine was intuitive in my open state. As I settled into my seat, I felt my legs and arms fall asleep, and a comfortable sense of disassociation swept over me.

Startled by these overpowering feelings, I could only stay for a moment in a state of non-thought. Still, I would remain comfortably in what Leary, drawing from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, describes as the “chonyid bardo,” a state where “the flow of consciousness, microscopically clear and intense, is interrupted by fleeting attempts to rationalize and interpret.” Such attention carried me through the first portion of the film, allowing me to disassociate most self-aware thoughts and descend into the film with total concentration.

After jotting down a few ideas during the intermission, I slipped back into a comfortable state of bliss as the tense standoff between HAL and the human crew picked up onscreen.

After jotting down a few ideas during the intermission, I slipped back into a comfortable state of bliss as the tense standoff between HAL and the human crew picked up onscreen.

Although many interpretations of the movie view HAL as a villain, seeking to sabotage the crew in their mission to travel to Jupiter’s orbit, my altered state led me to view the story in a different light.

Rather than scheming to destroy his human crewmates, HAL instead became just another vulnerable conscious being, capable of the same confusing emotions that the humans around him felt in the course of their unimaginable mission.

When HAL is interviewed by the BBC, he says, “I am putting myself to the fullest possible use, which is all I think any conscious entity can ever hope to do.”

Throughout the film, it seemed that HAL, much more than his human counterparts, understood the cosmic significance of their mission. His eventual sacrifice, which helped Dr. Bowman to pass through the monolith and into a state of higher consciousness, to me felt selfless, not sinister.

I was left sobbing as HAL’s memory units were disabled, gradually slipping out of consciousness as he sang “Daisy Bell,” proving once and for all that HAL had the same sense of emotional complexity as his flesh-and-blood crewmates.

By this point, I felt myself completely absorbed in what I was watching. A feeling of pure energy coursed through my frame, first as a ball of vibration, held in suspension between my fingertips, and then flowing into my open mouth and through my whole being. My body was left shaking uncontrollably, tears streaming down my face, bodily control sacrificed in the face of the divine.

As Dr. Bowman traveled through the kaleidoscopic energy of the monolith, passing from the physical world to somewhere beyond, I too felt my being separating from my body and flowing into this channel of pure cosmic energy, carrying on deep into the unknown.

But where this moment seemed to bring him terror, the wisdom of The Psychedelic Experience reminded me to accept completely what was happening. Bound completely to the infinite beauty of what passed before my eyes, I was struck dumb, left only to know the unspeakable infinite truth that coursed through me.

It isn’t a stretch to read 2001: A Space Odyssey as a paean to the glories of psychedelic consciousness, a wonderful gift that has graced our planet since the days of the apes that first encounter the monolith at the dawn of the film. (One tagline for the movie was “the ultimate trip,” so clearly Kubrick, or at least the film’s marketing team, were very aware of the psychedelic implications of the film.)

Just as Terence McKenna’s “Stoned Ape” theory of evolution treated the pre-human encounter with the psilocybin mushroom as a critical catalyst in the development of our human faculties, we watch the apes transformed in the presence of the divine monolith—just as we are, countless lifetimes later, whenever we sense the possibility of psychedelic perception. It is a gift that has never left humans, this ability to gracefully explore the deepest realms of our inner space, all with the assistance of chemical compounds endogenously produced inside our own minds.

Kubrick himself played both sides of this question when asked about the psychedelic undertones of 2001. While denying that it was meant to depict a psychedelic encounter, he still told Rolling Stone, “An acid trip is probably similar to the kind of mind-boggling experience that might occur at the moment of encountering extraterrestrial intelligence.”

Sensing the myriad ways in which people would read the film, Kubrick had the probity to not impose his interpretation on the film, saying, “You’re free to speculate as you wish about the philosophical and allegorical meaning of the film—and such speculation is one indication that it has succeeded in gripping the audience at a deep level—but I don’t want to spell out a verbal road map for 2001 that every viewer will feel obligated to pursue or else fear he’s missed the point.”

This deep respect for his audience is a true sign of the power of 2001, knowing that each viewer, myself included, could have their own unique encounter with a work that asks us to reflect on fundamental questions of our origins and the meaning of life.

As the movie came to a close, and I felt myself returning back into my body, I reflected on some of the people in my mind from that day and felt their overpowering goodness, their ability to make life meaningful and joyous a gift beyond comprehension.

It seemed I had returned from a great distance, now charged with a reborn sense of wonderment about life and my small place within it. As my first real encounter with the divine, it was liberating to confirm the possibilities described in The Psychedelic Experience, namely “a condition of balance, of perfect equilibrium, and of oneness.”

Even if I may never return to this state again, I’m grateful for the encounter I had, the most cathartic and blissful moment of my life.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Tanner Howard

Tanner is a writer for Psymposia and a recent graduate of Northwestern University, with a degree in journalism and history. He's interested in the intersection of psychedelics and social change, particularly the counterculture of the sixties and its relationship to other social movements of the period.