A Channel for Magic: Ralph Hood’s Mysticism Scale and the Occult Roots of the Johns Hopkins Psychedelic Research Program

Psychologist Ralph Hood’s study of serpent handling and mysticism helped legitimize the study of psychedelics. So why doesn’t he want them approved for medical use?

A Channel for Magic: Ralph Hood’s Mysticism Scale and the Occult Roots of the Johns Hopkins Psychedelic Research Program

Appalachian psychologist Ralph Hood’s study of serpent handling and mysticism helped legitimize the study of psychedelics. So why doesn’t he want them approved for medical use?

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Roland Griffiths and his research team at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine faced a conundrum when organizing the first therapeutic study of psychedelic drugs in three decades: how would they measure a correlation between the “trip” and any potential health benefit? Ascribing a specific medical outcome to what is often an indescribable event—the burden of the regulatory administrators—would be no walk in the park, and so a meeting was scheduled. A recognized authority on the psychology of religion, a college professor named Ralph Hood was summoned to help solve the problem.

In the late 1990s, Hood was flown to California to meet with Bob Jesse, head of the Council on Spiritual Practices, along with psychedelic researchers Bill Richards and Roland Griffiths. The group discussed the best available measures for assessing psychedelic effects and came to the conclusion that Hood’s M-Scale—a 32-item questionnaire meant to measure mystical experiences—would be an ideal tool. “It would allow them to do two things,” Hood said. “They could fight the argument that [the measurement was] just objective nonsense because they could say, ‘Hood’s scale has shown that you can identify mystical experiences across religious traditions—among Buddhists, Hindus, Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, and people who have no religious beliefs.’ And you can identify that same experience with people in deep meditative prayer; people who have it occur spontaneously; people who practice the presence of God with a kind of contemplative prayer; and among people who take drugs, right? So not one of those things [exclusively] produces the experience. There are occasions.”

The questionnaire didn’t just provide Johns Hopkins researchers with a data-collecting device they could use to justify dispensing mind-blowing doses of psilocybin; it also reliably predicted how effective they would be in treating what appears to be a wide range of emotional disorders. “That gave them the ability to go to quality journals,” Hood said. “It became the most widely used measure and has been wonderfully successful. It’s been translated into over 20 different languages and every time you get a similar pattern of responses.” The closer the scale came to indicating that the volunteer achieved what researchers consider a “complete mystical experience,” the more likely they were to undergo a radical shift in outlook. Not only did they feel less terrified of life and death, less depressed, and more open; more often than not, they felt completely transformed. Forgiveness took priority over resentment. Sweeping increases in clarity and optimism followed what felt like a divine epiphany.

Unlike earlier treatments for despair, the benefits of psilocybin are attributed to a roughly eight-hour experience that, according to Hood’s scale, fills one with a sense of wonder; a feeling that all things are alive; a sense that nothing is ever really dead; an essential oneness with all things; and a brush with an ultimate reality that feels sacred, timeless, and holy. This was the closest thing to a genuine spiritual awakening that science had ever purposely induced and documented, and the researchers could seemingly repeat the procedure on command. When the findings were published in 2006—many of the volunteers rated the experience as the single most important event of their entire lives—it changed the course of medical history. Health professionals in high places described it as “near-miraculous.” Some in the field argued they had a responsibility, helpless as they were in the face of a severe mental-health crisis and epidemics of opioid abuse and deaths of despair, to get psychedelics out into the market as soon as humanly possible—they might restore faith in medicine. All of this was pre-pandemic, a factor which would only exacerbate the misery.

Griffiths knew he was onto something. A tidal wave of research into altered states of consciousness followed, accompanied by an endless stream of effusive reporting that stands in stark contrast to the acid-scare whipped up by the Nixon administration in the 1960s. No more would psychedelics “destroy your chromosomes” or make you strip naked and jump from a ten-story window. From online workshops on “navigating the ancestor realms” to classes on “getting the most out of microdosing,” the so-called psychedelic renaissance—tailor-made for the influencer age and its hyper fixation on amassing followers—is well on its way to becoming a multi-billion dollar industry. Major sports figures, popular journalists, and famous actresses all now attest to the healing powers of psychedelic therapy. Even scientists are beginning to sound more like salesmen, suggesting psychedelics might “help us save the planet,” “fight fascism,” and “heal the world.”

Despite the hype, Hood sees the potential of psychedelics being squandered if limited to for-profit medicine. “I was confident that it would produce these effects, but I’m not interested in psychedelics to find a medical use, because that leads to government medical control.”

Academic institutions such as Johns Hopkins, Hood says, are focusing too much attention on the medical application of psychedelics, at the expense of their potential as agents of spiritual transformation, juxtaposing the approaches of two groups: The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, which is taking a medical approach to psychedelics, and the Council on Spiritual Practices, which wants psychedelics to be accepted in religious and spiritual contexts. “I’m not opposed to it [medical research] but I think it loses the vision of the Council on Spiritual Practices. The thing that drives medical research is pharmaceutical companies and they are happy to find any condition for which they can have a patented drug that you have to take for the rest of your life. So that model is drastically wrong.”

The strange thing about mystical experiences is that we have no explanation for how they work. They also can’t be accounted for by any science or history book. If you are curious about the ways in which our distant ancestors interpreted disembodied voices and ecstatic visions, you’ll have to look someplace else: in the Bible and other central religious texts. According to Roland Griffiths, such experiences are found not just in the memoirs of Christian mystics such as the Spanish nun St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), but more than one thousand years before that, in the writings of the Neo-Platonist philosopher Plotinus. The New Testament, the so-called “Old” Testament, the sacred texts of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam—all of them contain descriptions of mystical-like experiences. “A large body of historical evidence,” Griffiths and his co-authors claim, “describes the use of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psilocybin mushrooms, for religious purposes.”

These ideas about the history of religion—the belief that mystical experiences are ancient and at the root of all religious traditions (sometimes called the “perennial philosophy”)—stem from the figures listed in the footnotes: Aldous Huxley, William James, Carl Ruck, and Ralph Hood. Once a fringe belief promoted by a handful of maverick academics, the idea that pharmacology played a major role in the origin of religion is now gaining popular currency, influencing not just billionaire venture capitalists but religious leaders and respected scientists.

Hood knows a thing or two about fringe religious practices. He’s been going to snake handling services for nearly forty years. And though he’s seen his fair share of fatal strikes, he believes that it’s every American’s right to get in touch with God however they see fit, whether that involves eating mushrooms or chugging mason jars of strychnine. Though many states have passed laws prohibiting serpent handling, Hood has testified in court that it’s prejudicial, arguing that we allow high risk behavior in secular activities as long as you’re a consenting adult. He’s demonstrated, for instance, in the same one year period, where two people died in Tennessee from serpent handling and ten died from whitewater rafting.

“Some of the laws are just stupid,” Hood said to me in his office in September 2019, leaning back in a swivel chair and responding with a candor unusual for someone in his position. “Kentucky is the dumbest. They were the first to pass a law. Kentucky law says, ‘It shall be illegal to use a reptile in any religious service.’ Now notice two things: The law is aimed directly against religion, which itself is unconstitutional. Secondly, it says ‘reptile,’ which is stupid, because that means if your kid brings a turtle to Bible study, he’s violated the law.

During the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century science became the vehicle for an assault on death. The power of knowledge was summoned to free humans of their mortality. Science was used against science and became a channel for magic. —John Gray, The Immortalization Commission

Although there’s no evidence that early Christians handled serpents, Hood made the case that they probably did. “They were in a desert environment. I think the church eventually stopped it because they didn’t want the lay people to have the power,” Hood said. “They wanted the priest to have the power. The deep, deep roots of Christianity in early pagan mystery cults is also denied. And yet, if you look and read carefully, it’s all there. We know all of the holidays are mixed up. To try to separate it like it emerged out of nothing is crazy.”

☤

Ralph Hood is seated at his desk on the third floor of a tall gray and brown building on McCallie Avenue in downtown Chattanooga. Now in his fifth decade of teaching psychology, he had just returned from delivering a lecture on William James in Poland when we met up. One of the most recognizable figures in the psychology of religion, Hood is a mainstay at academic conferences, as well-known for his idiosyncratic attire—a ball cap, tie dye t-shirt, and blue jeans, occasionally dressed up with a suit jacket—as for his eccentricity. An obsessive researcher and prolific author, his unpretentious way of talking belies a vast knowledge of cultural and intellectual history.

Though he created the measurement device that lent psychedelic research much of its current credibility, Hood warns of an “American psychological imperialism“ exclusively reliant upon measurement, preferring to treat experiences of God and transcendent realities as fertile ground for scientific exploration. Rather than an incubator for pharmaceutical products, Hood sees in psychedelic research indications of something more radical: the possibility that mystical experiences provide evidence of a larger reality, the terra incognita described by shamans and ancient mystics.

The walls of his office are neatly lined with bookshelves and photographs from his field research. A macabre scene with an occupied coffin centered in the frame caught my eye as I scanned the perimeter of the room: a small group of southerners stand clustered around a corpse clutching handfuls of deadly serpents. The men all look possessed, their eyes beaming with supernatural radiance at the casket and its ghastly inhabitant. “I just came back from the homecoming in Middlesboro which has been a long-time [serpent] handling church. Fourth generation. I used to love to go to these homecomings, everything was cooked from scratch and real butter. Now they’ve got a bucket of chicken from Walmart—gross shit.”

Shortly after moving to Tennessee in the early 1970s, Hood began to hear stories about a local church where people danced themselves into a frenzy handling poisonous serpents. “2 Drink Strychnine At Service and Die In Display of Faith,” The New York Times reported from nearby Carson Springs on April 10, 1973. Newspapermen from around the country began filing into the mountains to see worshippers wrap rattlesnakes around their arms and necks, ecstatically shaking and slashing on guitars like hillbilly bacchae. When he saw a colleague from the sociology department on television attributing the entire thing to ignorance, he decided to investigate the matter himself. “I started to locate the churches and I just found them amazing and fascinating. Those who say it’s cultural deprivation don’t understand the rich culture of Appalachia. I know all of the dark sides, but I get furious when they stereotype these people and don’t realize what great power they have. Some of the wisest people I know live in the Appalachian Mountains.”

There was hardly a better place for a young Jamesian to find himself. The mountains surrounding Chattanooga are not just the birthplace of American serpent handling churches; they are also at the center of a region that is a repository of weird old ways, where religion and magic and medicine are sometimes still intertwined. As late as the 1970’s, folklorists were still discovering herbalists such as Tommy Bass and Clarence “Catfish” Gray using cures dating back to Dioscorides’ notebook. The foundation of organized medicine was in fact built by an army of nameless farmers and folk healers, midwives, root cutters, and rural druggists who scavenged the earth searching for materials that might alleviate suffering. Plants, roots, trees, gums, resins, minerals, bugs, fungi, and a slew of animal venoms—lizards, fish, scorpions, snakes, leeches, and toads—were cut, smashed, smeared, tasted, and tested for any potential medicinal or magical use. The skillful use of poisons for hunting and healing was critical for survival, and thus a highly valued specialty.

These human guinea pigs passed their knowledge of drugs down through the oral tradition for thousands of years until the first doctor-philosophers—Galen, Dioscorides, Theophrastus, amongst others—wrote the information down and organized it into the earliest texts on pharmacy and toxicology. Before the spread of industrial medicine, people in mountainous and rural areas continued these traditions, relying on popular health books, hearsay, personal experience, and the Appalachian “granny women” and midwives often condemned as witches and abortionists.

The ritual handling of snakes is also nothing new. Weston LaBarre, an anthropologist that wrote early studies of both peyote cults and serpent handling sects, called Appalachia “the last stronghold of archaic religiosity in America.” Its associations with shamanism and spirit possession are apparent to anyone watching a serpent handling service. Video footage recorded by Hood and archived at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Library shows congregants in the highest pitch of religious frenzy conjuring the Holy Ghost with cymbals and guitars, belting out Hank Williams’ “I Saw The Light” 1 and Ralph Stanley’s “I Am The Man, Thomas” while simultaneously speaking in tongues, dancing in circles, drinking poison, sobbing and jerking, and handling fire. If no musicians show up, the service is canceled, Hood says.

“It can look chaotic to an outsider, but it’s more like jazz,” Hood said.

In Mystery Cults of the Ancient World, Hugh Bowden—Professor of Ancient History at King’s College London—highlighted similarities between serpent handling churches and the pagan mystery religions of Ancient Greece (agrarian cults that practiced ecstatic rites and secret initiation ceremonies, the symbol of the ancient mysteries, the cista mystica, is a snake emerging from a wicker basket). “It would be possible to depict snake-handling services as almost indistinguishable from ancient Bacchic cult,” Bowden wrote, with their shared focus on cultivating divine mania, though they are by no means identical. “Serpent handlers may be said to be achieving an epiphany, that is, an intuitive grasp of reality, a perception of the essential nature or the meaning of themselves, religion, and God.”

Bowden’s footnote is a paper by R. Hood titled “When the Spirit Maims and Kills.” Serpent handlers are not a bizarre aberration, Hood argues, they are a “deviant religious sect” who believe the fear of death can only be defeated through direct confrontation, an idea with obvious parallels to psychedelic thought. Their practices ensure the tradition remains decentralized, grounded in scripture, and immune to routinization. “Common sense dictates that such a practice, both dangerous and lethal, cannot sustain a denominational success.” Handling is a subversive worldview, a therapeutic ritual, and a sincere declaration of faith, all-in-one.

Serpent handling churches started popping up spontaneously around the turn of the century when Appalachia began to be “developed.” As the machines made their way up into the mountains—the missionaries and their “railroad religion” not far behind—some of the mountaineers sensed unwelcome change on the horizon. The industrial economy and its values were alien to a lifestyle centered around agriculture and its cycling seasons. Industry meant bosses. Bosses meant time clocks. And time clocks meant remote control, a subtle way of grooming and mechanizing what they saw as a natural—if not always “efficient”—way of life. At best, this meant (a state of) dependency. At worst: another form of slavery. Already a sign of the devil, the serpent naturally lent itself to their suspicion around technology such as television and other tokens of progress—a potent symbol of a silently poisonous influence. “The capitalist system that coal mining introduced,” David Kimbrough, a scholar with Appalachian roots argues, “was a frightful distortion of the mountain social and economic order and snake handling represented a form of supernatural retaliation.” 2

“The [serpent handling] movement really came out of three great strains in America,” Hood told me. “One is the great Holiness movement. Here’s what Holiness is in a simple psychological sense: your life should be lived as an outward manifestation of a spiritual transformation. Holiness people refuse to have their life changed by an imposition from the outside. They know when to say no. And then, the great fundamentalist tradition. I wrote a whole book on fundamentalism because I think the psychologists writing on it got it all wrong—it’s the religion that even people who are religious love to hate. The argument is that fundamentalists take a literal interpretation of scripture, right? That’s not true. I don’t know of anybody who does that. What makes a fundamentalist a fundamentalist is that they don’t believe in what I call an ‘intertextual view of life.’ You look in my office, and there’s all kinds of books. And one book talks about another book—that’s the intertextual crap. But the fundamentalist, whether he’s a Muslim or a Christian, says, ‘My book is authority. I try to live by this book and I’m not interested in what Ralph Hood has to say about it.’ All of that is combined with the Pentecostal movement which says that religion is better felt than told.”

If serpent handlers have their own St. Paul it’s George Went Hensley, a hard living ex-moonshiner who founded the mother church of serpent handling—the Dolly Pond Church of God with Signs Following—in Birchwood, Tennessee in 1910. “Right up the road here on White Oak Mountain, he was struggling with his faith, and he saw a rattlesnake. The Gospel of Mark says that you can take up serpents, so he did. He was amazed that he wasn’t bit, that nothing happened.”

Hensley became an official Church of God minister in 1912 and six years later established the East Chattanooga Church of God. One Sunday in the summer of 1955—at a meeting near the Florida-Georgia line—he was struck on the wrist while trying to cram a large rattlesnake back into an empty lard can. As his arm swelled and turned jet black, Hensley dropped to his knees, blood erupting from his mouth. After four hundred some-odd bites and seventy-four years, he finally met his match. The death certificate listed the death as a suicide; handling reptiles was and is illegal in Florida.

In Them That Believe—the result of decades of research and direct observation—Hood and his colleague Paul Williamson showed how the Church of God later attempted to conceal its roots. As word spread through newspaper accounts and word of mouth, scoffers arrived carrying milk cans and gunny sacks of cobras and other deadly serpents, daring the handlers to raise them. More and more people began to handle and more and more people got bitten and died. The resulting body count produced sensational headlines and a headache for church leadership pursuing growth or “worldly success.” They tried to stop it, but what Hood calls the “renegade” churches—“Kentucky’s full of them and they’ve all got Church of God in the name of some kind”—continued to handle. The Church of God eventually split, creating the Church of God of Prophecy, both of which endorsed serpent handling up until the late 1950s.

“They finally took a stand against it officially and now they’re almost like the most adamant anti-polygamous of the Mormon Church. There are renegade polygamous groups all over, in Texas and in New Mexico, and the church hates that. When Charles Conn wrote Like A Mighty Army which is the official church history, we got him to put a footnote in the first edition. By the third edition, he admits that serpent handling was once endorsed by the Church of God.”

After exiting into the adjacent room and shuffling through some boxes, Hood returned with a battered metal sign proudly displayed between his arms like a lottery check: Birchwood Church of God of Prophecy. “They wanted to deny it ever happened or existed and so I kept this piece of evidence. I refused to allow them to erase their past. They tore down what should be one of the greatest places and stories and so I stole their sign.”

Serpents have been associated with healing since antiquity, so Hood’s obsessions are more coherent than they might first appear. A snake curled around the staff of Asclepius, the Greek god of drugs, has symbolized the practice of medicine for nearly three thousand years. The hero of an enormously popular healing cult, Asclepius was the god of medicine for a reason: his vast knowledge of plants and poisons and how to use them. His entire backstory, including where he was born, are all centered around his status as a drug god. “The myth of Asclepius,” the historian Ido Israelowich explained, “connected him to Chiron, the wise centaur who was skilled in the knowledge of drugs and lived on Mount Pelion which was renowned for its herbs. Being skillful in the use of drugs was, therefore, expected of Asclepius.” 3

The wooden staff symbolizes wisdom and goes back to a story about Apollo and Gaea’s daughter Daphne being transformed into a laurel tree to escape his advances. Laurel leaves were said to induce the oracular trances at Delphi, and its berry, the baccalaureus, gives us the roots of the modern words ‘Baccalaureate’ and ‘Bachelor’ (as in Bachelor’s degree).4 The staff therefore represents higher learning and the attainment of secret knowledge pertaining to drugs and the healing arts. Asclpeius could raise the dead; restore fertility; heal the blind; cure cancer; help you get a boner, or fix your broken arm. None of this was free. The ideal all-in-one physician, pharmacist, and therapist, his serpentine avatar slivered into the drug-induced “dreams” of his patients delivering diagnoses and cures on the spot. The surviving testimonies of the healing epiphanies of Asclepius, Georgia Petridou explains, “carry the unmistakable hallmarks of a divine revelation and often…the signs of a mystic experience.”

Hood’s interest in the macabre was no coincidence. He had been reading the work of William James. Though now mostly remembered as an early Pragmatist, James developed an uncommon but highly-influential way of studying religion, one that laid the foundation for the psychedelic research at Johns Hopkins. Published in 1902, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature—a transcription of his Gifford Lectures of 1901-1902—provided a philosophical framework for analyzing and contextualizing extraordinary states of consciousnesses. By focusing on the “abnormal psychical visitations” that he saw as being common to every tradition, rather than on the outward or institutional differences, James broke new ground in providing a natural explanation for the origin and essence of religion.

It will be asked, can we make this a really experimental study? Must we not content ourselves with simply watching these fleeting images as they rise and pass away? Is it possible to induce hallucinations? And, if possible, is it safe? —Edmund Gurney to William James

“The first thing James did,” Hood said, “was challenge people who thought you could dismiss powerful religious figures because they were strange, and the term he used was medical materialism. He did something that I strongly support even today, though it’s debated ad nauseum: he made a distinction between interpretation and experience. He thought that religion was largely about interpretation, and that if we start going there, we argue and fight forever. But what if, he said, the interpretation is built upon some kind of fundamental experience that is common across traditions and differentially interpreted. And then he came to these final lectures where he said that the root and center of all religion is mysticism. That got me going and I’ve been stuck with it for 48 years.”

☤

When William James died in 1910 his legacy was in serious jeopardy. A pioneering philosopher and towering intellectual presence at Harvard where he counted Gertrude Stein, George Santayana, and W.E.B. Du Bois amongst his students, James offered the first psychology course in America and was twice elected president of the American Psychological Association. The rare celebrity academic whose lectures drew large crowds and whose books were enjoyed by specialists and laymen alike, his Principles of Psychology (1890) was the first psychology text authored by an American to be read widely internationally. His reputation as a talented writer and respected thinker was world-renowned, admired by Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. He was stylish and unquestionably brilliant with a knack for distilling complex philosophical debates into everyday language. James’ studies are a field unto themselves these days, the papers, biographies, journals, and scholarly treatises too numerous to mention.

He also spent his entire adult life investigating psychic mediums and paranormal phenomena, hosting seances in his home and emphatically defending faith healers and mind-curers from the licensing boards. “James was way ahead of his time,” Hood told me. “He supported not licensing physicians. He said it will wreck it. And when they tried to license it, he said, ‘You’re doing this to keep other kinds of healers out. I want the faith healers. I want all of those people to be there. Let these options compete. Don’t close them out.’” A champion of the weird and eclectic and a predecessor to figures such as Rupert Sheldrake, long before Terence McKenna came onto the scene, James was vigorously challenging the academic and scientific establishments’ authority to determine what is and what isn’t deemed credible or ordinary, generating condemnation from his colleagues and accusations of occultism.

In many ways, Roland Griffiths and Bill Richards—the principal architects behind the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research—are simply continuing the paranormal or ‘psychical’ research that began with James and his European allies at the dawn of the Victorian age. From telepathy to religious conversion (or what they call a “quantum change”), out-of-body experiences, and reports of alien encounters, psychedelic research opens a Pandora’s box of unexplainable phenomena that can turn hardened skeptics into knee-jerk conservatives. James’ empiricism, Hood emphasizes, included the immediate content of consciousness: dreams, visions, and mystical experience.5

Influenced by popular comparative works like The Golden Bough—the search for the origins of religion was a ‘major scholarly preoccupation’ at the time—as well as lectures by religious scholars and self-styled mystics such as the Indian philosopher Swami Vivekananda, James became fixated on reconciling science and religion through what he perceived as correspondences between the accounts of mystical experience documented in sacred texts and reports of drug-induced trance, such as those of Benjamin Paul Blood. Prestigious medical journals of the time commonly featured fantastical accounts of hallucinogen use by “chemical intellectuals” such as the British psychologist Havelock Ellis who interpreted their effects through the prism of lighting machines and Romantic poetry with its elaborate mental imagery. 6 Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception eventually solidified in the minds of most Americans the archetypal psychonaut or white European intellectual engaged in self-experimentation.

At the same time, anthropologists studying peyote cults and what they saw as magic or “primitive” religions recognized that psychedelics sharpened perception, a potential generator of “savage” mythology and “superstition.” The seeds of the psychedelic theory of religion popularized by Gordon Wasson were sown.

A trained physician and the son of a Swedsborgian theologian, James believed that science was headed down a narrow path of development that would eventually snare humanity in its own trap. In the final decade of the nineteenth century, along with graduate seminars focused on “mental pathology” and altered states of consciousness—his lectures at Harvard addressed everything from trance states to hysteria, as well as dreams, hypnosis, hallucinations, demonic possession, intoxication, and witchcraft—James began offering courses on the ‘Science of Religion,’ developing ideas that would eventually land in The Varieties of Religious Experience.7

Pure religion, James said, wasn’t found in the pulpit, but the extreme experiences that shaped the psychology of its “pattern-setters,” the ultimate point from which all of its philosophies flowed. Sunday school, easter egg hunts, singing hymns, and everything else your average American knows about religion—including the Holy Bible itself—were little more than habits, James argued, passed down through imitation and folklore. At best these were afterthoughts or reverberations of the sacred. This was what he called ‘the second-hand religious life’ and he had little interest in it; theological formulas are secondary products, James said, “like translations of a text into another tongue. Feeling is the deeper source of religion.”

Like nearly anything else, when religion is taken to an industrial scale, it loses its authenticity. Experimentation goes out the window. Free-thinkers and mystics are pushed out (or beheaded) and the rest head for the exit. That’s how orthodoxy works. But each religion has a mystical strain at its core, James believed, an heirloom seed that contains its structural DNA. If all of the books and their ossified institutions were wiped out, the mystical experience would just generate them all over again. Would it be possible, he wondered, to initiate one of these experiences in a lab setting, with all of its ‘inner authority and illumination’ intact? If so, they might be able to measure and harness its practical fruit: changes in behavior and outlook.

Polarizing from the moment it was published, The Varieties of Religious Experience was impossible to ignore. Its critics claimed James had drifted from scientific psychology into pure speculation or mysticism. Here was a full-blown defense of miracles and the supernatural from a Harvard professor, an extended apologia for his own paranormal research. To his admirers, James was simply studying a phenomenon like any other, with the tools that he had available. Why should the mystical experience be any different from, say, a seizure? Any so-called ‘science of the mind’ that couldn’t account for these extraordinary experiences—surely some of the most consequential, biologically and culturally-speaking, events in all of human history (the conversion of St. Paul alone is an undoubtedly monumental event: Christianity as we know it wouldn’t exist without it)—wasn’t worth the name of psychology. A favorite of Aldous Huxley, D.H. Lawrence, and Jorge Luis Borges, James’s masterpiece also inspired Aleister Crowley and other occultists passing their philosophies off as some lost “sacred science” of the Etruscans or Ancient Egyptians.

“The whole tribe of mind-curers, theosophists, and the like will take great comfort in his concessions,” the New York Times remarked at the time, encapsulating the revulsion of some in the intelligentsia. If every looney with a vision was a potential prophet, what was there to separate the deranged from the divine, the witch doctors from the St. Teresa’s, John’s, Peter’s, and Paul’s? By ignoring the everyday—institutions and your average believer—and focusing in on the outbursts of a small number of (possibly unwell) authority figures, addicts, and outright religious cranks, James had created little more than a gross caricature, religion was something much more ordinary. Mysticism wasn’t the essence of anything (except madness). His blending of the scientific with the spiritual, however highbrow and eloquently expressed, would only embolden the magicians. “It is hardly to be imagined that these lectures will have any general operation that is favorable to religion,” the Times concluded.

Its impact went well beyond anything James could have imagined. Explicitly singling out drugs as being useful for inducing mystical experiences (James himself had experimented with a variety of narcotics), The Varieties of Religious Experience eventually oozed from under the doors of religious studies departments out into the counterculture, becoming a staple for the highbrow stoner—the book is mentioned by name in Huxley’s Brave New World—and spiritually-minded psychologist alike. When fighting Harvard’s ultimately successful campaign to oust him from the university in 1963, Timothy Leary presented himself as flamekeeper of the Jamesian tradition. In a campus lecture delivered one year before he was terminated, Leary warned against the dangers of monotheism and Western science, which he said was focused on “manipulation of the environment.” A new, expanded view of reality was necessary, he said, and accessible through the experience of psilocybin, which catalyzed an internal rebirth. “I am scared that we are moving towards an anthill civilization,” Leary said. “Unless the aim of life is experience, we are mere puppets playing out roles in complex games.”

Though he started out wanting to cure mental illness, Leary quickly enlarged his vision to total human transformation. “We tried to operationally redefine the old teachings,” he wrote in 1973 from San Luis Obispo Prison, “and to offer an experimental Neo-Platonism.” His understanding of history convinced him that the psychedelic experience was ancient and vital to the ‘great philosophy-generating cultures of the past.’ Humanity would finally ‘evolve into a higher wisdom’ after learning to ‘dial, tune, focus, program, and reprogram your brain.’ Seeking to place psychedelic experiences within some kind of credible framework, Leary and Walter Pahnke, a PhD student of his, discovered Walter Stace’s book Mysticism and Philosophy. Building on the work of James, Stace outlined a phenomenology of mysticism in which experiences were separated from their interpretations and systematized.

A British philosopher and Princeton University Professor, Stace argued for what he called ‘causal indifference’—a crucial concept for the current studies at Johns Hopkins—the idea that what causes or triggers the experience is irrelevant. Whether it’s psychedelics or the sunset, though there are certain things you can do to facilitate or help occasion the experience, what’s important is the experience itself. Furthermore, these experiences formed a universal ‘common core’ of religious experience, Stace said, an invisible psychological link underlying different faith traditions. The forms and varieties of religion seen throughout history and across the globe were simply the infinite cultural expressions of altered states of consciousness.

Stripped of impurities like laws and institutions, mystical experience could now be isolated and scientifically analyzed. A young professor in Tennessee took note, placing Stace’s categories into what psychologists call a Likert scale. “So what James says,” Hood told me, “is that we don’t want to look at the proximate cause of phenomena, right? It may be that certain religious triggers are associated with epilepsy, but even if they are, it doesn’t tell you about the fruits and the value of those experiences. So that got me interested in looking at the psychology that quickly dismisses people who are pathological, mentally ill, or disturbed by saying, ‘Well what are they disturbed about, and what are they actually responding to that is real?’” Hood did factor analysis and showed that you could identify states and measure them.

Thus the divorce between scientist facts and religious facts may not necessarily be as eternal as it at first sight seems…the rigorously impersonal view of science might one day appear as having been a temporally useful eccentricity rather than the definitely triumphant position which the sectarian scientist at present so confidently assumes it to be. —William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience

The paper was published in The Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion in March 1975, solidifying the mystical experience as a valid scientific concept. Science wasn’t exactly replacing religion, as some would argue, but it was beginning to reformulate it in its own image.

☤

Mystical experience as a measurable phenomena didn’t emerge (or evolve) without its critics. Ann Taves, Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies at UC Santa Barbara and the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship,8 says that the conclusions derived from the research at Johns Hopkins rely heavily on the idea of a universal “mystical experience,” a theological concept that functions as a catchall category for a variety of possibly unrelated mental states. Hood’s questionnaire—based on this spiritual belief that Taves says was elaborated over the past one hundred years—doesn’t just influence the volunteer into seeing the experience as a positive one, it also suggests and reinforces their assumption that the mystical experience is a distinct or sui generis one.

“If scientists fail to make a clear distinction between scientific claims based on empirical evidence and theological claims based on revelation or tradition, they risk setting mystical experiences apart from other similar experiences on theological rather than scientific grounds. They have no scientific basis for making theological claims regarding the common core of all religions or the presence of an ultimate reality that unites them,” Taves wrote. These broad and unstable categories, she says, limit our ability to uncover the mechanics of consciousness and how these experiences actually work.

Some believe that these theological premises are being obscured by researchers who have both an ideological (and in some cases: financial) interest in bringing psychedelics to market. Add to this the fact that psychedelics are now being hyped as the answer to all of our problems and a troubling picture emerges. Did the scientists of religion, attempting to model the natural sciences and systematize religions, accidentally synthesize them, creating a new, scientific subgenre of Christianity that they themselves could believe in? What’s really happening at Johns Hopkins might be the flowering of a new psychedelic spirituality, grounded in Jamesian mysticism, with psilocybin “therapy” replacing the ancient initiation ceremony. Dr. Rick Strassman calls it “the psychedelic religion of mystical consciousness.”

“It’s a messianic movement,” Strassman told me. “They want to bring about a utopia, and in this case, the messiah is the mushroom.”

Strassman is not just a veteran psychedelic researcher—his investigations into DMT in New Mexico in the late 1980’s were the very first post-prohibition psychedelic trials in the United States—he was also the first person Bob Jesse asked to help initiate the mystical experience trials before Roland Griffiths and Johns Hopkins signed on. “Bob Jesse discovered the rave culture in the Bay Area in the early 1990s and he got bit by the bug big time,” Strassman says. “He thought that this was a path to utopia. He stopped working at Oracle, got a big severance package from Larry Ellison, and just went on this mission. And he’s been kind of nonstop since then.”

Psychedelics, Strassman says, don’t have any inherent mystical or spiritual effects—those are caused by set and setting: specific musical playlists, sensory isolation, and filtering the results through questionnaires like the M-Scale. The current psychedelic movement or “renaissance,” he says, is essentially the emergence of a new mystico-scientific religion—“camouflaged by scientific studies and statistical firepower”—with its own Moses (William James) and cult vocabulary (psychedelics “occasion” effects; adverse effects are now “challenging”; flashbacks are “reactivations”; “and if you read the articles, they all start to borrow the same language.”) There’s the philosophy of James, Strassman says, and then there’s his theology, which was inspired by his connection with Swami Vivekananda.

“Vivekananda was preaching a universal religion—not just anybody’s universal religion, his universal religion—which would promote utopia. There would be no more sectarian strife. The way you could do it was by positing a universal religious experience which all major religions shared and that was biological or “hardwired” so, how could you deny it? If you accepted it, all the sectarian differences would kind of melt away. This was consistent with and supported James’ idea of a universal religious experience that was a formless, content-free, no-self state.”

Strassman worries specifically about Judaism, which is “particularistic” and therefore incompatible with a universal religion. The Hebrew Bible doesn’t contain any contentless, selfless, ego-loss experiences free of time and space, he says, and as a result, is viewed by researchers as inferior. “The existence of a universal religious experience is a theological solution,” he said.

Other researchers are moving away from mysticism for their own reasons. Matthew Johnson, a professor at Johns Hopkins Center on Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, has warned his colleagues against adopting frameworks “drawn piecemeal from mystical traditions” that might alienate potential customers. “Ultimately, we want them [insurance companies] to cover this stuff,” Johnson told Vice. “And there is going to be an issue with covering religious therapy. The point is, someone could make an argument against it.” It is also inappropriate, he says, to introduce “meta-religious” belief systems such as perennialism (or “the common core”) into therapeutic practice. Johnson is a paid advisor with at least seven different companies developing psychedelics for medicinal use.

Hood freely acknowledges the limits of language and even his own scale for capturing the sacred. Some things you just have to try for yourself, he says. “Say you’ve never tasted a lemon before and ask me what one tastes like. ‘Well hell, I say, I don’t know. Have you ever had an orange? It’s like that, but sour.’ No matter how much I talk, can you walk away saying that now you know what a lemon is like? The answer is no—go taste the goddamn thing. Once you taste it, all of the words don’t matter. There’s no substitute for experience. You will know the answer on the basis of your experience, and what that experience has elicited in you. We are caught as intellectuals with the notion that it’s all in the words.”

One explanation for such widely reported claims of experiencing God and transcendent realities, he says, “is simply that they do.” People don’t just search for the sacred, they respond to it, and his scale simply and accurately measures that response, whether it’s occasioned by drugs, isolation, meditation, prayer, or gazing at the sunset. Though culture is certainly a factor in how people choose to express these experiences, no mystic would mistake the interpretation for the experience itself. Those who know don’t say, Hood says, and those who say don’t know.

“I never ever said that I measured mystical experience. I don’t have that much hubris. I measured people’s response to an experience. Maybe you lied. Or, maybe my questions were good enough so that you said, ‘I’m going to mark it this way because there’s something there that rings true.’ That means it is more than just a mark on that piece of paper. One of the arguments that people have made against my scales is that it’s difficult. Double negatives. My response is that the people who respond to it never have that problem. It has high reliability. I’m always open to the fact that you lied, but it’s hard to mask that. If you did lie on the other scale, fine, but then that’s just stupid.”

Despite the shortcomings of experimental science, Hood believes that most drugs could safely be in the marketplace if people are educated about them. However, he does worry about the commodification of psychedelics and what may happen if the pharmaceutical industry—prone to baseless hype and deceptive advertising—controls the market. Strassman agrees that Johns Hopkins’ approach is too reductive and that there’s a danger of turning psychedelics into “super Prozacs.”

“The United States has always granted absolute freedom of religion,” Hood said, “it’s a unique country. The Supreme Court has never challenged or commented on the theology of serpent handling or the theology of multiple wives. But here’s what it says: ‘You can believe whatever you want. And the only criterion is sincerity. If you sincerely believe that God is affecting you, you can do it.’ But, if they have an overriding interest, then they can regulate practice. So, can they regulate drugs? Well, my position generally is almost a libertarian with respect to drugs. I think almost all drugs should be legalized, and then you shouldn’t take any of them. But, [the question is] who controls it? It’s kind of like moonshine. The people in Appalachia say, ‘How can you stop us from making liquor? We’ve made it our whole life. We know how to make it. It should be legal.’ So I think drugs should be in that vein.

These [serpent handling] churches are wonderful. You go to the church, and they will say, ‘Who’s got the Word?’ And if you ain’t got the Word, then sit down! If nobody’s got the Word, they go home! I think colleges like that would be great. Wouldn’t you like it if somebody stood up to lecture, and someone said, ‘You ain’t got the Word today, we are leaving!’ Religion should fill you with passion. You can be married but not in love, right? So it’s a passionate religion that should move you and fill you and be the entire aroma of your life. And I think that psilocybin does that for some people. Johns Hopkins has shown that there are people out there saying, ‘I want this reckoning that there’s something more.’ And what psilocybin does is, for many people, it gives them the mystery, the sense that there’s something more. One of the things that Johns Hopkins needs to do—and it’s very expensive—is look at people who have had this experience and then follow them throughout their lives. See what they do with it, and if it changes them, because everything gets abused real quickly.”

Hood’s fears appear to be well-founded. Psychedelic research labs around the world are now teaming up with venture capitalists to “make the world a happier place” by developing what Compass Pathways—the first publicly listed for-profit psychedelic company in the United States—calls the mental health care clinic of the future.

Compass created controversy when they misled a member of Johns Hopkins into sharing their research under the auspices of being a non-profit venture, leading to a public rebuke and suspicion around the stated goals of their enterprise. The eccentric German billionaire and futurist behind Compass and atai Life Sciences, Christian Angermayer, claims that he wants to extend human life by a century and put psychedelics into the hands (and mouths) of the “more than one billion” people suffering from crippling depression around the world. He also owns an impressive collection of ancient artifacts related to the Greek mystery religions. “There is more and more evidence that psychedelics were a foundation of western civilization,” Angermayer told a journalist for the Financial Times. A psychedelic enthusiast obsessed with religion and human immortality, Angermayer believes that psychedelics might also treat “collective mental health issues” and diseases that “we don’t even have a name for yet.” Things like “being afraid of the future” and “not feeling at home in the world anymore.”

Rather than enabling humanity to “evolve into a higher wisdom,” as Leary and others envisioned, psychedelics could instead provide nations with new and more effective techniques of population control, as Aldous Huxley predicted in Brave New World. Huxley wasn’t alone in foreseeing a dystopian state wherein psychotropic drugs played an essential role. The esteemed microbiologist and writer Rene Dubos also warned, in Mirage of Health, of a very-near future where vending machines full of tranquilizers and mood stabilizers chemically subdue a miserably bored and health-obsessed population. Complete freedom from disease and suffering, Dubos argued, is incompatible with the process of living. Applied retroactively, Angermayer’s utopian pharmaceutical regime might snuff out the entire history of music and art, leaving a sterile and lifeless uniformity.

Are you willing to be sponged out, erased, cancelled, made nothing? Are you willing to be made nothing? dipped into oblivion? If not, you will never really change. —D.H. Lawrence, “Phoenix”

“The spiritual model is a radically different model,” Hood told me. “Nobody I know of goes to church on Sunday to get wine in a dry county. It’s about what it triggers and evokes in you. ‘The poet said, ‘Put away the car when life fails, what’s the use of going to Wales?’ It’s because you have no meaning. I don’t like the diagnoses of depression or turning this into a clinical thing. It will destroy everything about it.”

☤

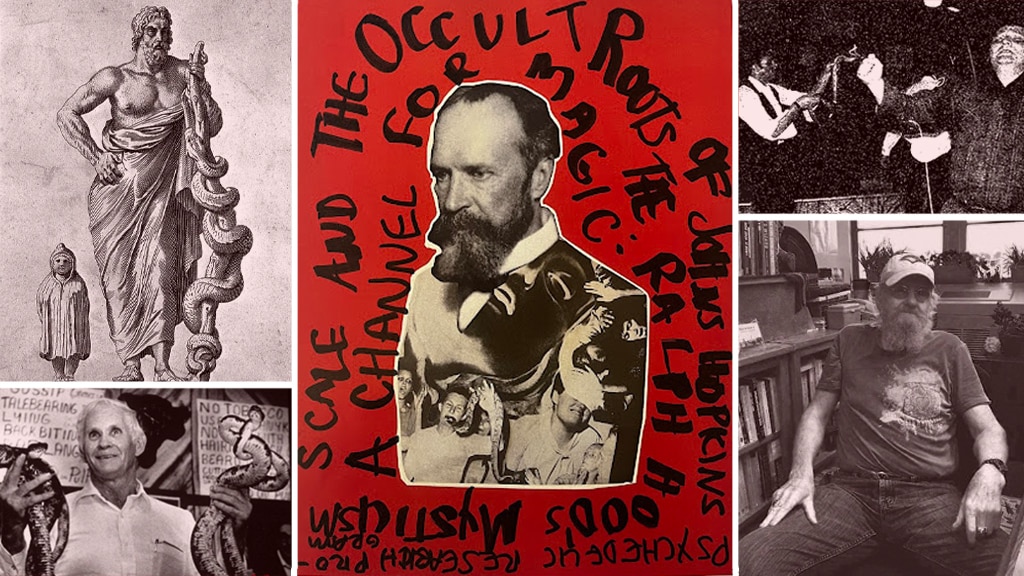

Banner collage of William James and snake handlers by Guy Blakeslee.

Travis Kitchens

Travis Kitchens is a writer from Kentucky. His writing has appeared in the Baltimore City Paper, Christian Science Monitor, and other outlets. In 2014 he volunteered for one of Johns Hopkins' psychedelic clinical trials.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.