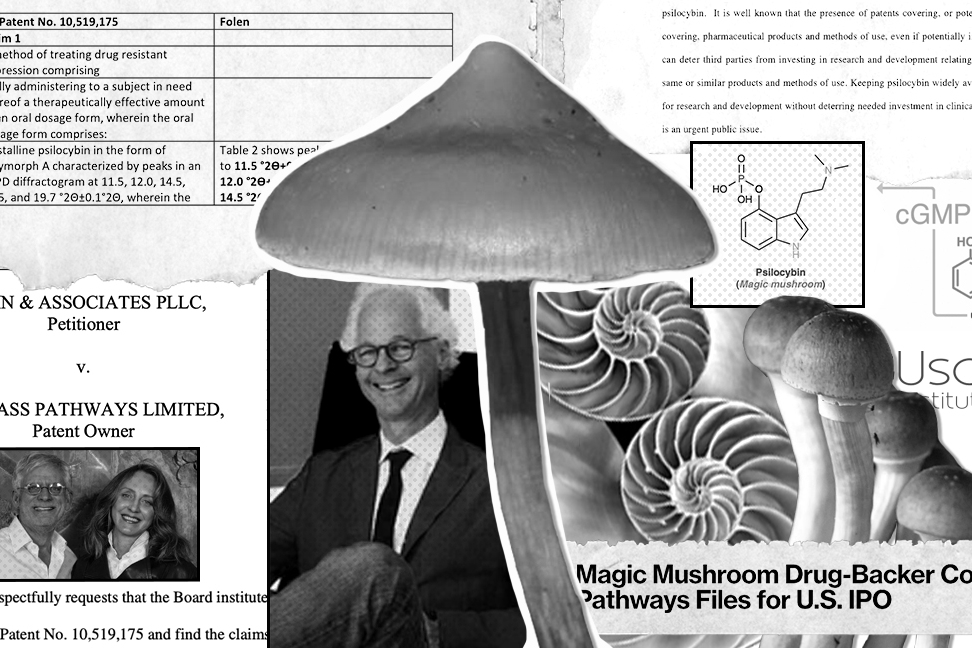

As COMPASS Pathways continues its attempts to build a psychedelic monopoly, Usona Institute keeps publishing open research

Since COMPASS Pathways filed for a controversial psilocybin patent in 2018, Usona Institute has consistently placed its research findings in the public domain.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Since 2019, the Usona Institute—a nonprofit medical research organization which conducts research on psychedelic substances for the alleviation of depression—has openly published six papers on manufacturing psilocybin and psilocybin-mushroom-related tryptamines. (Linked at the bottom of this article.)

The information contained in these papers includes scalable routes for synthesizing psilocybin, identification of different crystalline polymorphs of psilocybin (psilocybin molecules arranged in various crystal structures) suitable for clinical development, and syntheses and biological evaluations of tryptamines found in most psilocybin-containing mushrooms.

Usona has released all of these publicly available papers since the for-profit mental health company COMPASS Pathways filed a controversial patent in October of 2018. COMPASS’s patent covers the proprietary use of what the company claims is a unique psilocybin formulation, for use in conjunction with a psilocybin-assisted therapy protocol for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Reporting for Fortune, Jeffery M. O’Brien explained that COMPASS filed a patent in October of 2018 which had 27 claims of novelty (note: in order to obtain a patent for an invention, the patent claim must contain a novel innovation).

At the recommendation of a patent attorney, Carey Turnbull—a board member of Usona Institute and the President of the Heffter Research Institute—approached a team of chemists and psychiatrists to review COMPASS’s patent claims. They determined that COMPASS appeared to be attempting to patent LSD-inventor Albert Hofmann’s method of producing psilocybin. In addition to discovering LSD, Hofmann was also the first to invent a method for producing psilocybin in a lab. Turnbull challenged COMPASS’s patent claims as “prior art”—information that has already been made available to the public—through the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and COMPASS withdrew all 27 claims.

The European Patent Office also rejected a patent filed by COMPASS, citing prior art by Hofmann, the pharmaceutical company Sandoz, and others, according to O’Brien’s reporting.

COMPASS resubmitted their patent application to the USPTO with 10 claims of novelty, which Turnbull objected to on the same grounds as his prior challenge. COMPASS once again withdrew the patent. COMPASS finally submitted an application with just one independent claim of novelty and 20 dependent claims, which was approved Dec. 31, 2019.

Turnbull continued to dispute the approval of this patent through Kohn and Associates, and through Free to Operate (FTO)—a company Turnbull created to “further the goal of keeping psilocybin widely available for research and development” for the treatment of conditions like depression, according to a July 7, 2020 response to COMPASS’s attempt to dismiss the dispute against their patent. “One way [FTO will pursue this goal] is to seek to invalidate patents such as the patent at issue which may serve to deter or burden research into psilocybin and its many beneficial uses because they appear to cover known forms and uses of psilocybin.”

The response goes on to say that keeping psilocybin widely available for research and development is an urgent public issue. And, “it is well known that the presence of patents [like COMPASS’s] covering, or potentially covering, pharmaceutical products and methods of use, even if potentially invalid, can deter third parties from investing in research and development relating to the same or similar products and methods of use.”

The argument in Turnbull’s and Kohn and Associates’ petition disputing COMPASS’s patent was ultimately denied by the USPTO on August 20, 2020.

“Having considered the evidence and argument presented in the Petition, we determine Petitioner has not shown it is more likely than not that any of the challenged claims are unpatentable as obvious over the cited art,” the USPTO decision document states.

The denial decision asserts that, “[A] patent composed of several elements is not proved obvious merely by demonstrating that each of its elements was, independently, known in the prior art.” The patent dispute petition had cited the works of V. A. Folen, Dave Nichols, Robin Carhart-Harris, and Mintong Guo as prior art reproduced in COMPASS’s patent.

“[I]t can be important to identify a reason that would have prompted a person of ordinary skill in the relevant field to combine the elements in the way the claimed new invention does,” the USPTO decision continues. “Although Patent Owner does not address the substance of Petitioner’s challenge, after considering the arguments and evidence presented in the Petition, we find Petitioner has failed to show sufficiently that the combination of references teaches or suggests each limitation of claim 1 [of COMPASS’s patent].”

After months of dispute, it appears that COMPASS will get to keep the patent for its synthesized psilocybin formulation. With this patent secured, COMPASS has filed paperwork for an initial public offering (IPO) through the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. It intends to list on the Nasdaq Global Market under the symbol CMPS and hopes to raise $100,000,000 through its IPO.

In response to a Twitter post in which the COMPASS patent was compared to proprietary insulin formulations and asthma inhalers created to increase corporate profits, Graham Pechenik—a patent attorney focused on IP law and strategy in the cannabis and psychedelic industries—wrote that he believes the comparison is accurate, and that he is worried that “big psychedelics” will share similar issues to “big pharma, big tech, big ag [agriculture], and other monopoly-heavy industries.”

I definitely think those are reasonable comparisons, and I too worry that “big psychedelics,” if it comes, will share all the same problems of big pharma, big tech, big ag, and other monopoly-heavy industries. /1

— Graham Pechenik (@calyxlaw) September 13, 2020

“I’d like to believe that the investment and attention that come with patents can help accelerate broader awareness, access, and acceptance of psychedelics, and that this will both broaden the space for what already exists, and open a new space for innovations,” Pechenik wrote. “But I do worry that ideal ‘everyone wins’ scenarios get defeated in practice by people and companies who…put profits over humanity. Patents are inherently monopolies, and monopolies inherently lead to imbalances and inequalities.”

Company secrets such as the synthetic psilocybin formulation that COMPASS won the right to keep are attractive to investors, but—as noted above—“can deter third parties from investing in research and development relating to the same or similar products and methods of use.” These kinds of early-mover advantages are exactly what investors want to see in order to feel secure that they will make money from investing in a company. But, the discouragement of other third parties to research—in this case—psilocybin is exactly what many in the psychedelic research community hoped to avoid when it became clear that corporate interests had their eyes on psychedelic medicine.

Although Usona Institute provided no funding towards the patent dispute and has no control over the dispute petition, the issues presented in the dispute represent many of the open science values with which Usona Institute and Turnbull are aligned. Both parties—as well as 132 other individuals and organizations—signed onto the Statement on Open Science and Open Praxis with Psilocybin, MDMA, and Similar Substances. This statement asks signatories to use prior psychedelic research and knowledge for the common good and to share freely whatever related knowledge they may discover and develop. Notably, COMPASS did not sign onto this statement. Neither did COMPASS’s largest investor, Atai Life Sciences, or any of its C-suite.

As more psychedelic companies file to go public, flashing their intellectual property at eager investors, Usona Institute’s strategy provides an important counterpoint to the direction in which the tides of industry appear to be flowing.

“Usona remains committed to sharing our work publicly under the Open Science model, because we believe that openness, transparency, and collaboration will allow this field of scientific knowledge to progress most efficiently, and our drug development work continues to move forward at full speed,” a Usona Institute spokesperson said of the nonprofit’s philosophy. Usona will also provide Current Good Manufacturing Practice psilocybin to qualified researchers at no cost, if they submit full protocol and other documentation for review and evaluation.

Usona Institute’s openly published papers on manufacturing psilocybin include:

Enzymatic Route toward 6‐Methylated Baeocystin and Psilocybin

Published: 31 May 2019

Published: February, 2020

Published: February 20, 2020

Scalable Hybrid Synthetic/Biocatalytic Route to Psilocybin

Published: February 26, 2020

Direct Phosphorylation of Psilocin Enables Optimized cGMP Kilogram-Scale Manufacture of Psilocybin

Published: July 1, 2020

An Improved, Practical, and Scalable Five-Step Synthesis of Psilocybin

Published: August 1, 2020

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Russell Hausfeld

Russell Hausfeld is an investigative journalist and illustrator living in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism and Religious Studies from the University of Cincinnati. His work with Psymposia has been cited in Vice, The Nation, Frontiers in Psychology, New York Magazine’s “Cover Story: Power Trip” podcast, the Daily Beast, the Outlaw Report, Harm Reduction Journal, and more.