I was an MDMA manufacturer in the ’80s. Then fled the country as a fugitive for 20 years. | Part 1

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Voices—male and gruff—yanked me awake. The bedroom door banged open. Heavy hands grabbed my arm and flung me face down, naked on the floor. Dust from the carpet filled my eyes and nose. An icy metal tube slammed into the back of my neck, in the soft part just below the skull. The barrel trembled with the hand that held it, and a drop of sweat splashed onto my ear. I tried to lie very still.

A brittle voice screamed, “D…E…A.”

Hands pulled my arms back, hauling at my shoulder joints until my chest rose off the carpet. My grunt surprised me. More icy metal squeezed the bones at the sides of my wrist.

When the hands suddenly let go, the side of my face smashed into the carpet. At least the gun was no longer shoved in my brain. The hands dragged me upright and guided me out the bedroom door.

They left me standing, handcuffed and naked, in my kitchen. I tried to hold the cold metal away from my back, but my arms tired. I could see more agents dumping out trash barrels in the backyard.

They had me dead to rights. It was a familiar story: An old friend was caught and threatened with a long sentence unless he gave them someone important. Me. He came with an agent and a wire.

It was my own fault. I had been one of the first to take advantage of “designer drugs.” Some chemicals that get you high, like MDMA, can be slightly changed in shape—thereby becoming a new and legal substance.

I had found an analogue of MDMA that had the same effects. I called it “heaven” because it was the hydroxyl analogue, MDHA. I had been manufacturing it in increasing quantities for two years—it was selling well.

But just a few months back, the DEA invoked a new law called the Temporary Scheduling Act. Using it, the DEA could place any substance in Schedule One for up to 18 months while they studied it to see if it really needed to be scheduled.

Now my drug, MDHA, had been listed and had the same penalties as heroin. I should have stopped manufacturing, but my partner had stiffed me, and I was under a lot of pressure from wholesalers. So I had gone ahead and set up one last batch. Now I was facing 15 years.

But my lawyer David had a plan. Only Congress shall make the law. Why was the DEA, the enforcement agency, the sheriff, making laws? David argued that temporary scheduling violated separation of powers and was therefore invalid. Actually, the law that Congress passed delegated the power of temporary scheduling to the attorney general, a member of the Cabinet, and thus, the executive branch. But the executive is not supposed to make laws—it carries out the laws.

To make matters worse, the attorney general then turned around and sub-delegated his authority to the DEA. It’s a dangerous situation when the enforcer can also make laws. Delegation of the power to schedule is particularly sensitive because it includes severe criminal penalties.

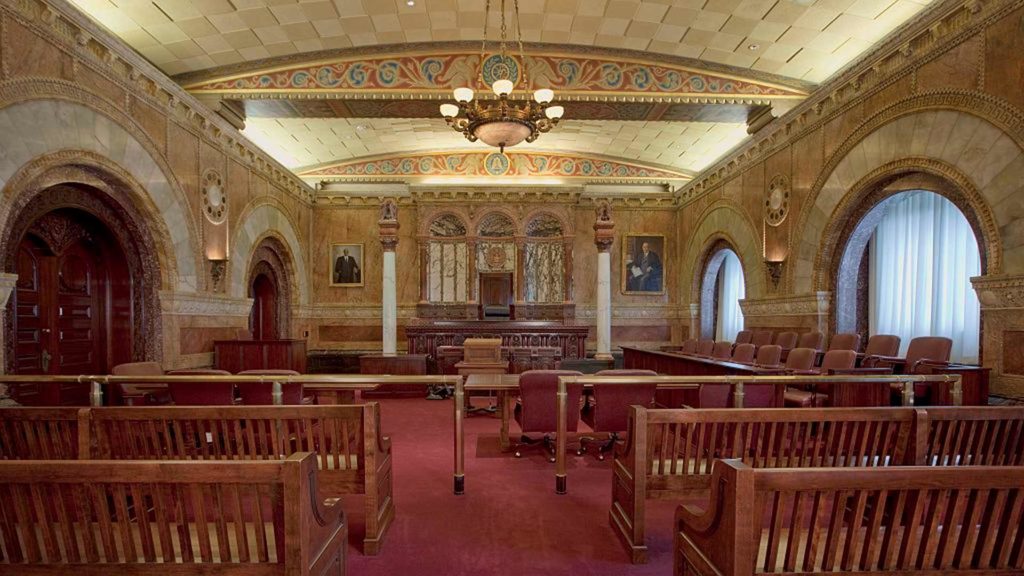

So David had written up the legal arguments in a document and submitted it to the judge. They came for me early on the day he was going to consider the brief. Guards wrapped me in chains, took me to the empty courtroom, and left me there.

I was alone in the halls of justice. The size of that room made me feel insignificant, as if the law was much larger than me or anyone else. There was no intimacy there; I hoped there was mercy.

I was perched on the edge of my wooden chair, uncomfortable, trying not to fidget. I felt foolish in my bright orange scrub suit. My life was at stake, and I was not allowed to speak. My presence was a mere formality.

The prosecution team came in and sat at a table about 20 feet away. Seven men in three-piece suits crowded together, whispering. I tried not to stare at them. The young prosecutor with the mustache from my first hearing was there. He led the team. He was here to vilify me, but he knew almost nothing about me. I was merely a case to be won or lost. My life went on his report card.

My lawyer hurried in as the judge entered. We all rose. The dais was high against one wall; the judge presided over us. He barely glanced at me. To him I represented a legal principle.

David whispered to me, warned about my demeanor. Don’t stare harshly at the judge. Be calm, but don’t smile. Act respectfully.

They began. The judge was lordly. The prosecutor was harried, nervous. My lawyer stood and stepped to the prosecutor’s table. They exchanged pleasantries and sheets of paper. The whole thing was too civilized. My patience was running thin, and my fingernails were bleeding.

The prosecutor stood and spoke. My lawyer stood and responded. They droned on. I needed to use the bathroom. The discomfort continued to build. The hard wooden chair was cutting into my buttocks.

Then everyone was silent. The judge rifled some papers and read a statement. He thought that the attorney general should not be able to make criminal laws. The judge said that the sub-delegation from the attorney general to the DEA was also improper and clearly violated separation of powers.

“Case dismissed.”

I was numb.

My lawyer was shocked.

The marshals came to escort me back to jail. I had to pick up my clothes and check out. They took off my chains. When we got to the courtroom door, I looked back. The young prosecutor was bent over the table, slamming the bottom of his shiny black shoe into the plush carpet harder and harder and harder.

A few days later, I received a note from David: “Government appealed. Papers attached.” My heart jumped when I saw the heading: Widdowson vs. United States of America.

No date was set, but David said that he had expected it and would handle it. I went about putting my life back together. I began a career in journalism, became a well-known personality on public access TV, and was also hired as a systems analyst on a huge research project at UT.

Ten months went by, and I nearly forgot about the case until I got a letter from David with a copy of his brief and some notes. He had presented at the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and felt that it had gone well.

Sure enough, a few months later, the 9th Circuit issued their ruling:

Delegation of the power to make criminal laws, even to the attorney general, violates separation of powers.

The dismissal of my case was upheld. I was still in the clear.

Not for long. This time David called me. The government had appealed again to the Supreme Court. It seems that there was a similar case in the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals. In that case, called Touby v. United States, the judges had decided that the delegation to the attorney general was perfectly proper—the opposite of my case. When two circuit courts disagree, the Supreme Court must step in to decide. So my case and Touby were put on the 1991 calendar.

The DEA had a real problem here. For years it had struggled with a way to combat designer drugs. How can you outlaw a chemical that hasn’t even been made yet? They had tried a law called the Federal Analogue Act which states that any substance that’s similar to an illegal scheduled substance, and has a similar effect, is itself scheduled. But similar in structure and similar in effect turned out to be nearly impossible to define, especially with harsh criminal penalties at stake. The Analogue Act was useless.

So they came up with temporary scheduling. It was all they had. If the Supreme Court ruled that temporary scheduling was unconstitutional, the DEA had no way to fight any new drug. We had them on the ropes.

In these cases, the Supremes studied the proceedings of the two circuit courts to come to a decision. They began deliberations. A few months later, I got the call; the Supremes voted 9 to 0 for Touby and against Widdowson. The DEA’s temporary scheduling of MDHA was proper. The DEA could now re-issue the warrant and re-arrest me.

David and I huddled. Officially, he advised me to stay and face the music. But then I asked him if he’d had clients who had run. Yes, he answered. I asked him if any were still free. He said yes. I asked, what did they do? He said they left the country. OK. Now I knew what I had to do.

Time to go.

You can read Rob’s full story in his book Heaven’s Tale: From Scientist to Kingpin, from Fugitive to Father

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

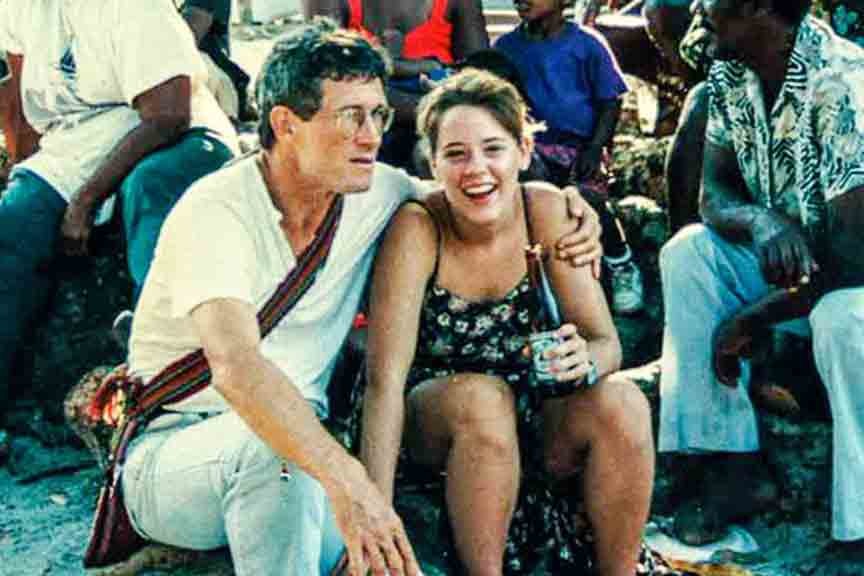

Rob Widdowson

Rob Widdowson has worn many hats—fugitive, scientist, jailbird, doctor, kingpin, and father. The adventures outlined here along with many more are detailed in his memoir, Heaven’s Tale.