Getting High is a Human Right: Reflections from Uruguay After Cannabis Legalization

Activists have started creating new spaces for healing, acceptance, heightened consciousness, and fun—a completely legitimate reason to do anything, especially get high.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Iwrite from Uruguay, quite far from God, and even further from the United States—though not the hegemony of neoliberalism. Uruguay has distinguished itself globally, especially from other nations in the Americas, with its significant atheist population, legal access to safe abortions, nearly 100% wind power, and of course, a landmark policy on cannabis. I have enjoyed smoking legal cannabis here, most of it grown at home or sourced through buying clubs. It’s strong, it’s cheap, and it’s also complicated.

The consumption of all substances here in Uruguay has been decriminalized for decades. Living here one month, slowly learning the language, my alienation and homesickness has been assuaged by adventures with LSD and pure MDMA crystals—a first in my tenure as a consumer. This I have been able to rather safely assume, given not only the presence of drug testing at parties, but also the publication of results in local papers. It’s been a truly unparalleled experience.

Legislative reforms around cannabis are happening all over the world, emboldening journalists to call this historical moment “the end of the war on drugs.” In many ways, this is true for an imagined class of largely affluent users of European descent—whose usage tend to stay away from “hard drugs” (a nonsensical phrase in the context of prohibition, that is in no way an indication of the potency of a substance, but rather a polite way to describe drugs that under-privileged people use). Uruguayan policy, much like that in the United States, has been constructed around this very narrative. As cannabis was legalized in efforts not only to displace narco-traffickers, but also to provide safety and security to its assumed otherwise law-abiding, middle-class consumers.

I am grateful for the global movement to reclassify cannabis, and similar movements for LSD, MDMA, as well as psilocybin. Courageous activists have started to undo the violence and devastation of draconian drug laws worldwide, creating new spaces for healing, acceptance, heightened consciousness, and fun—a rarely invoked, yet completely legitimate reason to do anything, especially get high.

However, legitimacy is the key word here. What are the legitimate substances? “Cannabis should be scheduled differently than heroin!” argue activists. Who are the legitimate traffickers? The state, not ‘thugs,’ said former President Jose Mujica—and increasingly more nations follow this doctrine. Who are the legitimate consumers? Good middle-class people living in developed countries. So it seems.

It is impossible to disassociate tranquilo nights of decriminalized candy flipping from the calls of the President of the Philippines, Duterte, halfway around the world: “If you know of any addicts, go ahead and kill them yourself, as getting their parents to do it would be too painful.”

The substance largely being used by these ‘addicts’ in the Philippines is a methamphetamine derivative called shabu. This is a drug that is cheap enough for ‘ordinary people’ in a country where a quarter of the population lives in poverty and where many cite their reason for use as—not for heightened consciousness, healing, nor fun—but to enable longer work hours to survive. It’s not unlike pasta base, a crude extract of coca leaf, here in the Río de la Plata region, which similarly came to prominence during Argentina’s economic crisis in 2001 and continues to be largely used by economically disadvantaged people here in Uruguay.

Middle-class drug reform activists call for drug reform in the name of optimizing life and love—look no further than this very blog for stories of how mind-altering substances have facilitated deliverance from dependencies, new intimate relationships, and spiritual connections. It’s gorgeous, it’s transformative, and it’s much of my truth too. But our universe(s) are not distinct from the so-called ‘drug zombies,’ as labeled by popular media outlets. I have come to know many of such humans through my work in New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C.—cities that have embraced the end of the drug war in many ways. Whether via creating access to sterile injecting equipment, diversionary programs for drug users, or even cannabis legalization.

These “zombies” are often users of the drug K2, or synthetic cannabis, popular due to its low price for aforementioned ‘ordinary people,’ psychedelic effects, and its lack of detectability by most toxicology screen tests that so often determine the fate of one’s probation, access to public housing, child custody, access to healthcare, life-saving medications, and employment.

It’s easy to label this as a zombie take-over, a tale of reckless and dangerous bad guys in lieu of accepting the complicated and deeply disturbing narratives of gentrification—the literal displacement of people, namely people of African and indigenous descent, from their neighborhood homes, quality schools, legal employment, and from access to legal highs. It’s quite easy to allow old-timey drug war propaganda and draconian legislation to dominate our imaginations once more, instead of having the difficult conversations about fiscal austerity or neoliberalism.

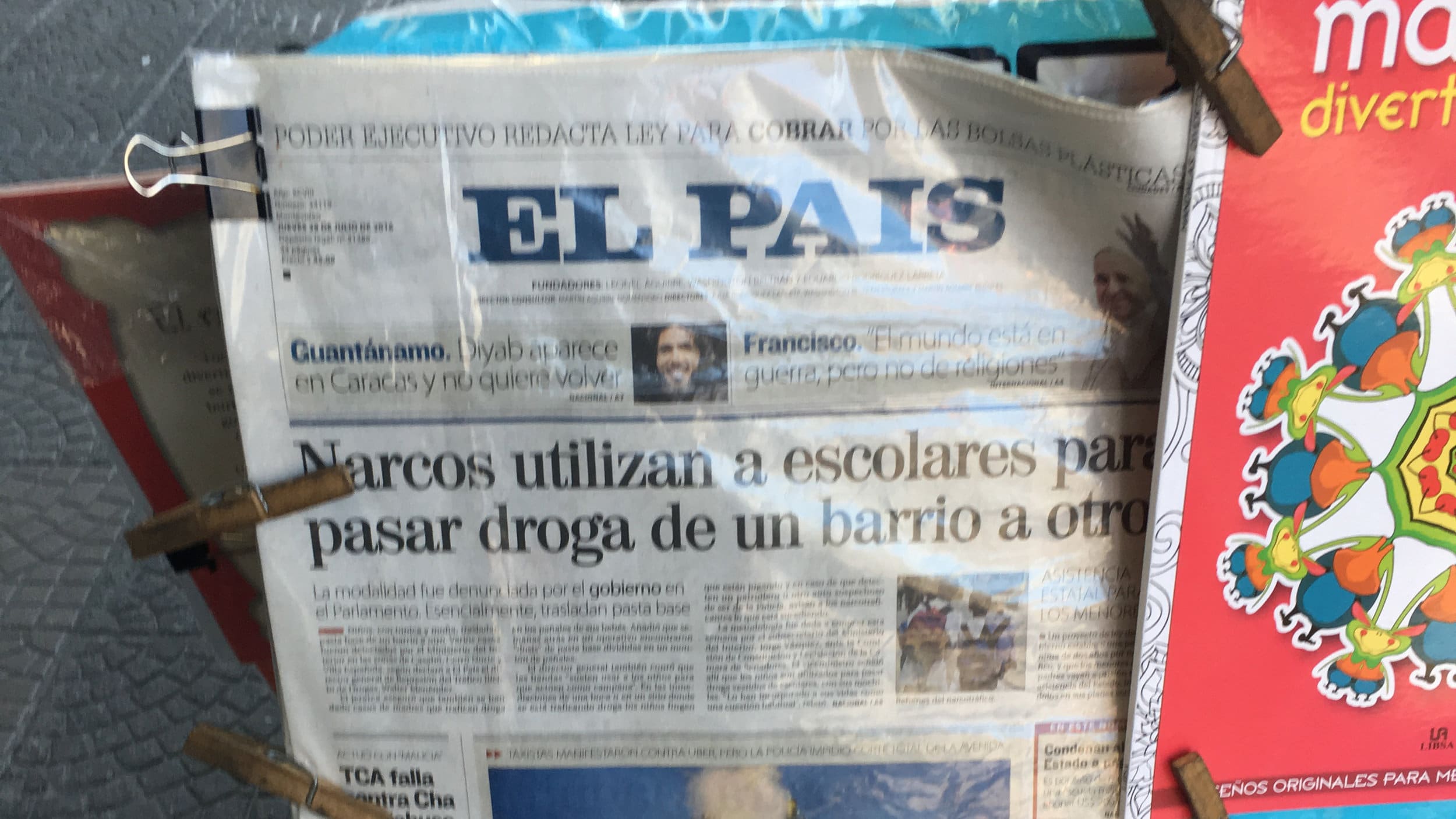

“Narcos utilizan a escolares para pasar droga de un barrio a otro,” Narcos used schools to pass drugs from one neighborhood to another, reads the headline of El Pais, a prominent Uruguayan newspaper from a kiosk as I walk through el centro. The article details how mothers traffic pasta base in the diapers of their babies and backpacks of their children. This is certainly a less-than-sympathetic image…or is it? It should be understood in the context of a world where members of the hustle economy are routine and systemic subjects of extrajudicial killing, or very judicial human rights violations, all the while pharmaceutical companies make billions selling the same shit. That (read: this) is a world in which legitimacy and illegitimacy are tied to a very specific type of safety and security. A safety and security belonging exclusively to bourgeois people and corporations that serve their every desire.

Who has a right to safety and security? And, in an increasingly unsafe world of economic insecurity, who has a right to escape it?

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Lindsay Roth

Lindsay Roth works as a grassroots organizer and social work professional with a focus on the rights of people who use drugs and people who trade sex.