It’s time to debunk prohibitionist narratives and calls for monopolies within psychedelic science

As venture-capital-backed, for-profit companies barrel into psychedelic therapy, the potential for the widespread privatization of psychedelic knowledge and profits looms large. Some researchers are so enthusiastic about medicalization by “any means necessary” that they’re resorting to prohibitionist historical narratives and calling for monopolies to push the agenda forward.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

As venture-capital-backed, for-profit companies barrel into psychedelic therapy, the potential for the widespread privatization of psychedelic knowledge and profits looms large. Some researchers are so enthusiastic about medicalization by “any means necessary” that they’re resorting to prohibitionist historical narratives and calling for monopolies to push the agenda forward.

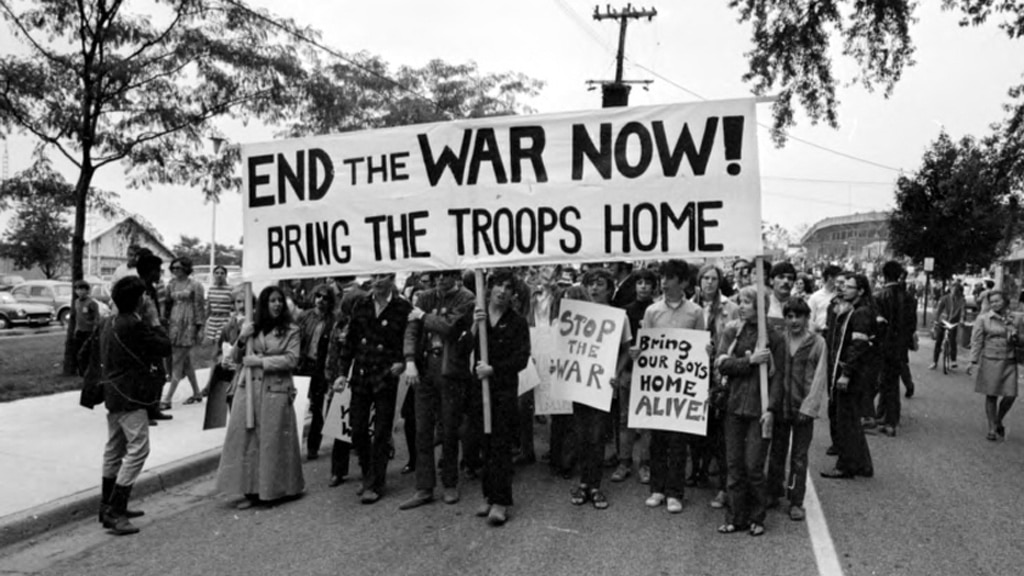

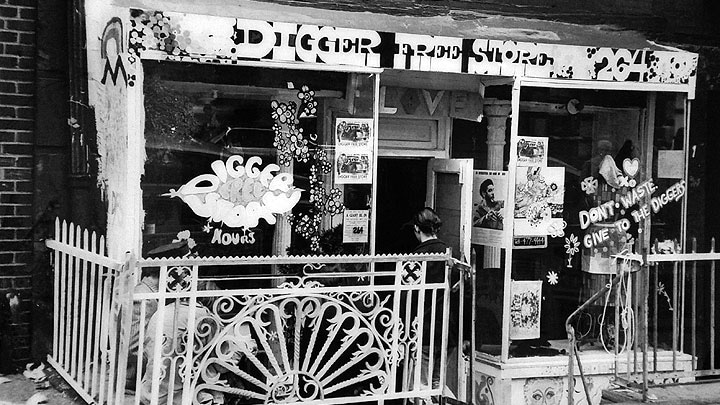

Since the early years of psychedelic awareness within the US, psychoactive plants, fungi, and compounds have presented a significant challenge to the status quo of dominant culture. Psychedelically-inspired actors opposed the war in Vietnam, provided food, clothes, and medicine to people in their communities, experimented with communal forms of living, and otherwise attempted to subvert the oppressive, hierarchical systems of what some of today’s psychedelic communities might term “the default world.” Amid the recent push for “psychedelic legitimacy,” numerous advocates of medicalizing and mainstreaming psychedelics have attempted to deny or suppress the vital connection between psychedelics and these legacies of rebellion. Hiding from the lineages of psychedelic political engagement not only whitewashes these histories, it does a disservice to the revolutionary potential of these compounds.

In a recent article for chacruna.net, Casey Paleos, a co-PI for the MAPS-sponsored MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for PTSD Phase 3 clinical trial, argues for commodified, for-profit approaches to psychedelic medicalization, like those we’ve seen from the venture capital (VC) backed, COMPASS Pathways. Relying on a series of spurious and counterfactual assertions, Paleos attempts to paint a picture of a “psychedelic renaissance” precariously balanced amid a prohibitionist paradigm set in motion by its countercultural forebears. In doing so, he discounts the vibrant psychedelic communities that have flourished throughout prohibition, and evidences his ignorance of the actual, verifiable histories of prohibition.

In his opening paragraph, Paleos asserts:

“[Leary’s] rallying cry urging Americans to “turn on, tune in, drop out” provoked a conservative backlash of such ferocity that our society is still reeling from it: Nixon famously identified Leary as “the most dangerous man in America,” declared the War on Drugs, and enacted the prohibition of psychedelics via the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.”

This line of reasoning has been used by countless psychedelic researchers and advocates, including Rick Doblin of MAPS. Unfortunately for them, this prohibitionist narrative doesn’t hold up to even the most cursory examination. Consider the following statement by John Ehrlichman, an advisor to Nixon:

“You want to know what this was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Even without this revealing insight into Nixon’s political motivations, we know that the actual timeline of prohibition was already well-underway prior to the 1967 “Be-In,” where Leary urged young people to “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

Consider the following excerpts from Acid Dreams by Martin Lee & Bruce Shlain:

In 1962 Congress enacted regulations that required the safety and efficacy of a new drug to be proven with respect to the condition for which it was to be marketed commercially. LSD, according to the FDA, did not satisfy these criteria.

In 1965 Congress passed the Drug Abuse Control Amendments, which resulted in even tighter restrictions on psychedelic research. The illicit manufacture and sale of LSD was declared a misdemeanor…Adverse publicity forced Sandoz to stop marketing LSD entirely in April 1966, and the number of research projects fell to a mere handful.

Spring of 1966. The Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency convenes yet another round of hearings in Washington, DC, to deal with the growing “LSD problem.” Chairman Thomas… proposes strict new laws aimed at “the pseudo-intellectuals who advocate the use of drugs in search for some imaginary freedoms of the mind and in search for higher psychic experiences.” Quick and drastic measures are necessary, Dodd asserts, because the LSD scourge is spreading at an alarming rate among America’s youth.

Amidst this atmosphere of near hysteria…Timothy Leary offered an olive branch to the politicians, suggesting that a moratorium on LSD might be appropriate…Leary announced he would urge everyone to stop taking LSD for a year if the lawmakers refrained from banning the drug. Repressive legislation, Leary warned, would usher in an era of prohibition that would be “much more onerous and anguished” than the moonshining days of the 1920s and 1930s. “We do not want amateur or black-market sale or distribution of LSD,” said Leary…

To insure good-quality LSD and proper use of the drug, Leary proposed seminars for high school and college students at special psychedelic training centers. These institutions would license responsible adults who wished to utilize LSD “for serious purposes, such as spiritual growth, pursuit of knowledge, or in their own personal development.”

The decision to curtail LSD experimentation was the subject of a congressional probe…in the spring of 1966 [and] was led by Senator Robert Kennedy…Kennedy insinuated that the regulatory agencies were attempting to thwart potentially valuable research…

Finally, on January 14, 1967, Leary uttered the allegedly prohibition-inducing words to a crowd of about 25,000 at a “Be-In” at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. The amount of historical revisionism underlying Paleos’ claim feels in-line with popular mainstream prohibitionist narratives.

Paleos goes on to claim that we are now at:

“…the cusp of something truly incredible: restoring the legitimacy of psychedelics in the eyes of the dominant culture…”

In doing so, he evidences his position as another privileged, white, male researcher. Dominant culture (i.e. capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy, industrial civilization, etc.) and its institutions are predicated on the notion that some of us are illegitimate merely by nature of our existence. There are systemic issues of access and oppression that underlie the status of “legitimate” when viewed through the “eyes of the dominant culture.” Calls to engage in “respectability politics,” and pretend our values are continuous with those of dominant culture are nonsensical and inherently exclusive to those of us marginalized by that culture. How many of us found ourselves drawn to psychedelic spaces precisely because we found ourselves threatened by dominant culture?

Paleos continues:

“[Doblin] did so by recognizing that long-lasting societal change of this magnitude cannot be imposed from without, as Leary sought to do; it can only be accomplished from within.”

Even if we ignore the oxymoronic notion of “long-lasting societal change” and the reality that societies are in a state of perpetual flux—even conceptual utopias require a “constant becoming,” as the fluctuating needs of humans and the ecosystems upon which they rely require constant re-balancing—the assertion that change “can only be accomplished from within” simply doesn’t hold up to historical analysis.

One need only examine the role of anarchists in the labor movement, radical abolitionists in the fight against slavery, draft resisters during Vietnam, the Polish underground during WWII, the Zapatistas in Chiapas, or countless other “outsiders” who secured widespread (if not long-lasting) changes to find gaping holes in the narrative of slow, gradual change as the only viable option. Whether we consider the roles of militant organizers such as Ella Baker, Stokely Carmichael, and Leonard Peltier; autonomous aid projects such as the Black Panthers’ community health clinics and Free Breakfast for Children programs, or; direct community resistance to extractive energy projects (whether in indigenous or industrial contexts), the assertion that changing the material conditions of society requires complicity with its most coercive and destructive elements fails on its merits. Even in cases where widespread change did come “from within,” we can usually find outside actors and radicals who presented the “undesirable end” of the negotiating spectrum, thereby forcing dialogue with more moderate actors.

Intent on emphasizing his belief in medicalizing psychedelics, Paleos says:

“[Psychedelics] have provided me with tools to achieve not the mere abatement of symptoms—which is the best that traditional psychiatric medications can hope to accomplish, when they work at all—but to effect true healing. It is hard to overstate the magnitude of the unmet need for effective treatments in the field of mental health care: suicide rates in the U.S. are currently the highest they have been in 30 years, and there are hundreds of millions of people suffering from deadly illnesses like major depression, drug and alcohol addiction, and PTSD, for whom conventional treatments have proven completely ineffective.”

In doing so, Paleos unintentionally exposes a blind spot in the logic of medicalization. While numerous sanctioned psychedelic researchers tout their belief that psychedelics can “effect true healing,” rather than mere symptomatic treatment, their fixation on the individual as a wholly-bound entity, divorced from their environment, misses the bigger picture.

While psychedelics may “effect true healing” of the individual, the mere treatment of the individual—without engaging the material conditions (e.g. housing, healthcare, policing, etc.) that contribute to the causes of their illness—offers little more than systemic symptom management, rather than a “cultural cure.” The notion that we can expect psychedelics to “cure” people who are systematically brutalized by the coercive, destructive, and traumatizing systems of dominant culture, without simultaneously working to change those systems is every bit as symptomatically-oriented as current psychiatric regimens.

Citing research by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Noam Chomsky observes that “the increasing mortality among middle-age whites…analyzed as ‘deaths of despair,’ [is] a phenomenon unknown in functioning societies.” Chomsky contextualizes the trends that Paleos seems to be referencing, stating:

“No war, no catastrophe…Just the impact of policies over a generation that have left them, it seems, angry, without hope, frustrated, causing self-destructive behavior.”

Driving this point home, Case and Deaton emphasize that the problem isn’t “access,” it’s the systemic features of American society: the “long-standing process of cumulative disadvantage.”

This systemic blind spot is commonly accompanied by an additional historical blind spot: the notion that everything would have been hunky-dory if only psychedelics had remained under the sole-dominion of researchers; if only psychedelics had never “escaped the lab.” Indeed, Paleos asserts:

“…it is hard to imagine where the field of psychiatry would be right now, had the psychedelic research that began to blossom in the 1950s not been truncated by the end of the 1960s; had Leary, in other words, adopted an approach subtler than storming into the lion’s den and poking the biggest cats he could find in the eye. How many lives ravaged by suicide, addiction, and violence could have been saved? How much suffering alleviated, or prevented?”

If we ignore Leary and just focus on the implicit (and unknowable) assertion that, by keeping psychedelics in the lab “lives ravaged by suicide, addiction, and violence could have been saved,” and suffering could have been “alleviated or prevented,” all we find is historical revisionism.

LSD, and psychedelics more generally, factored into a significant amount of political engagement, including the anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, environmentalism, the push for nuclear disarmament, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Diggers, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to name a few.

Writing for the MAPS Bulletin in 2009, Ralph Metzner acknowledges the widespread benefits of the psychedelically-correlated counterculture in numerous arenas. Metzner discusses the “therapeutic ‘course-correction vision’…[of] plant-based entheogens” in the context of the nascent social-movements of the 1960’s, offering poignant commentary on the ongoing significance of such vision. Recognizing that building new worlds requires transcending the familiar, albeit outdated, structures we live with, Metzner posits:

“Although these social movements were countercultural or even, at times, revolutionary, in that they challenged unjust, limiting or outmoded attitudes and practices of the dominant social order, it is important to recognize that being against something was not the primary intention behind these movements.”

Paleos’ suggestions that suffering would have been ameliorated by preventing psychedelics from spilling out of clinical settings and into the real world seems unlikely. I would contend that the amount of global suffering stemming from the unchecked systems of American capitalism, imperialism, and militarism would have been far greater without the catalyzing impact of psychedelics on the psyches of those involved in resistance movements. To lament the loss of a mythologized “research monopoly” is to turn a blind eye to the really-existing histories of suffering in the real world.

Paleos goes on to make unimaginative arguments, citing “access” and “economies of scale,” to justify his belief in the merits of working with COMPASS. As I’ve already demonstrated, access isn’t the real story, and it certainly isn’t the full picture, but I’ll take a moment to address his more concrete statements. Paleos claims:

“To address a public health need of this magnitude requires an enormous infrastructure, which will cost hundreds of millions of dollars to implement…The reality is that…a for-profit company is the only kind of organization capable of operating on this scale.”

He appears to be echoing the same sentiments that Michael Pollan offered at the recent Horizons conference, where Pollan boldly proclaimed:

“Capitalism is a good way to scale things up.”

Sure. Capitalism is a GREAT way to scale things up…if you ignore its “externalities” and don’t care about the “systemic risk” and disasters such externalities create, such as the 2008 global financial crisis or turning the planet into a smoldering wasteland. For those of us who know otherwise, it’s likely apparent that rather than buying into narratives of, “This is how it needs to be, because this is how it is, because this is how it’s always been,” we need to explore alternatives. In this context, the fact that Paleos makes no mention, whatsoever, of Usona—a non-profit organization that is working to make psilocybin available to researchers (and eventually therapists) at cost (or less)—is fundamentally inexcusable.

However, even if we ignore this omission and accept the vague assertion that legal psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy “will cost hundreds of millions of dollars to implement,” that doesn’t answer the question of why, in Paleos’ mind, this requires a centralized, top-down approach. In fact, the steps that some clinics are taking in order to provide ketamine-assisted therapy for PTSD involves a much more decentralized, horizontal approach. The training costs and material requirements of setting up treatment facilities are absolutely real, but that doesn’t mean they have to come from COMPASS or any other potentially-monopolistic, centralized player.

The case of ketamine clinics presents real-world evidence of how the costs can be shared by practitioners. Additionally, perhaps major psychedelic institutions could offer grants or loans to assist with those costs. There are likely a plethora of strategies where, even if the total, net expenditure is in the “hundreds of millions,” that figure would be distributed in a reasonable manner among numerous clinics/therapists. Does it really seem like that much of a stretch to imagine a world where Usona (and other organizations) could make psilocybin available for minimal cost to a diverse ecosystem of psychedelic clinics?

How would you feel if I told you that COMPASS has ties to the fracking industry, military contractors, multinational banks, and big pharma? This isn’t an abstract question, it’s the “real world,” and I’ll be detailing these connections in a forthcoming article. How do you feel that COMPASS seed investor Peter Thiel is also the founder and chairman of corporate spymaster, Palantir? Do we really want the people leading the medicalization of psychedelics into global society to have connections to a corporation that has a $41 million ICE contract? Is this what living in the “real world… and operat[ing] within the limitations of reality,” as Paleos puts it, should look like? Does this make you excited? If so, I have a few questions for you about access and systemic inequality.

If COMPASS’ investors and associates are responsible for some of the most violent and traumatizing technologies and policies in the world, then how can working with them provide meaningful treatment “to the millions of people in need of it”? Here, again, we find ourselves on the treadmill of psychedelics as systemic symptom management. It’s a null-sum game of enriching the very people responsible for systemic traumas by paying them for “curative” treatments, even as they cause the very traumas they’re treating. The COMPASS network is positioned to cash in on people coming and going, and key figures tasked with conducting psychedelic research seem eager to facilitate this arrangement.

While Paleos does “concede that the decision made by COMPASS to…refuse to sign The Statement on Open Science is troubling,” in doing so, he evidences his lack of understanding about the realities of the situation. Even if COMPASS had wanted to sign The Statement (a document asserting that psychedelic research should be carried out for the betterment of humanity rather than personal enrichment) its structure as a VC-backed, for-profit organization would have precluded it from doing so. The corporate structure of COMPASS means that it’s fundamentally unable to uphold the tenets of open science, even as its actions, such as applying for a methods patent and securing an exclusivity agreement for synthetic psilocybin, demonstrate that reality. Put simply, COMPASS’ structure is oriented towards building a monopoly, not practicing open science or sharing data. Peter Thiel, has even repeatedly asserted, “You shouldn’t compete, you should try to have a monopoly.”

Paleos concludes:

“To my mind, the growth of a for-profit industry around the delivery of psychedelic-assisted therapy is…a marker of the tremendous success the psychedelic movement has had in restoring legitimacy to the use of these extraordinary tools…and represents the solid ground this movement must have underneath it to have any hope of creating the changes this world so desperately needs.”

While I don’t disagree that there are ways in which psychedelics can help change the world, there are glaring issues with Paleos’ conclusion. This isn’t about your doctor’s ability to profit, thereby supporting herself by bringing in more money than she spends in the course of running a private practice. This is about handing over the keys to the most powerful mind-altering substances known to humanity to a group of venture capitalists who have repeatedly demonstrated that they will do whatever it takes to turn a profit.

Additionally, there’s no evidence that psychedelics by themselves, or in combination with psychotherapy, offer “any hope of creating the changes this world so desperately needs.” This is the main reason I have repeatedly asserted the dire need for systemic critique within psychedelic communities.

Without developing meaningful understandings of why the world around us is in the state it’s in, how can we possibly hope to change it? Leading up to the 1968 Democratic Convention, Abbie Hoffman famously threatened to dump LSD into the Chicago municipal water supply. The notion was resoundingly laughed into oblivion. Pushing the for-profit corporate-medicalization of psychedelics while avoiding coherent sociopolitical analysis strikes me as not only incredibly irresponsible, but as little more than a strategy that may as well be called Dose the Water 2.0.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

David Nickles

David Nickles is an underground researcher and harm reduction advocate. He has presented social critiques and commentary on psychedelic culture and radical politics, as well as novel phytochemical data from the DMT-Nexus, at venues around the world. David’s work focuses on the social and cultural implications of psychoactive substances, utilizing critical theory and structural analysis to examine the intersections of drugs and society. He is a vocal opponent of the mainstreaming and commodification of psychedelic compounds and rituals, believing that such approaches inherently obscure the liberatory potential of psychedelic experiences.