When I asked a psychedelic philanthropist how he thought plant medicines could aid in the climate fight, he cooed: “let’s get to oneness first, and the rest will work itself out.”

Of the problems least likely to “work itself out,” climate change might top the list.

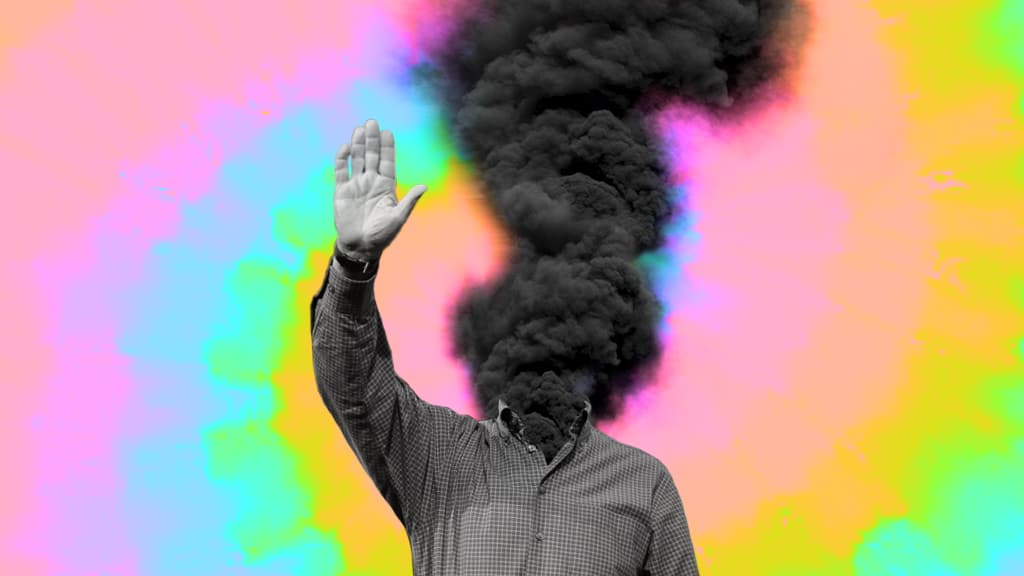

His magical thinking—a belief that one’s desires can influence the external world or that unrelated events are causally linked—did not surprise. The psychedelic movement has long been plagued by hand wave-y speculation that chemically-occasioned oneness will “save the planet” while failing to offer thoughtful analysis as to how.

Speaking at an online event, Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies Founder and Executive Director, Rick Doblin, offered that we need psychedelics to solve our environmental crises “because so far nothing else has worked.” He categorically dismissed decades of backbreaking political organizing without explaining how psychedelic use might overcome the perceived failures of the past. He and many others imply that individual experiences of molecularly-induced interconnectedness are somehow powerful and directive enough to rapidly decarbonize our energy, transit, and agricultural systems.

With billions of people in lockdown worldwide, our interconnectedness has never been clearer. Perhaps this is why some psychedelic pundits “love” COVID-19. They speculate that—much like a trip—our current viral oneness depatterns old thinking and reveals the true, interconnected nature of reality. Armed with this truth, they claim, we will avert catastrophe and as Charles Eisenstein posits, build a better world.

But as elected officials put profit over human lives, the Trump administration rolls back environmental legislation, white supremacy rears its head at home and abroad, and authoritarian regimes worldwide trample civil liberties, we are reminded that how society integrates this “trip” is determined by vested interests, powers that be, and—as Milton Friedman once famously put it—the ideas lying around. It is no coincidence that the same political and economic “ideas” that have prevented us from addressing climate change—like concentrated corporate power, structural racism, mistrust of science, and the dismantling of public services—are preventing us from effectively responding to this pandemic.

COVID-19 shows us that experiencing oneness will not solve our problems. Changing society is much more complicated than changing our minds.

Yet ever since LSD was first synthesized in the lab, prominent psychedelic leaders have preached that mind-altering substances would save the world. These millenarian narratives frame psychedelics as the best tool to help humankind avert imagined planetary cataclysm.

Such prophecies gained salience as real cataclysm arrived in the form of increasing ecosystem breakdown, from tropical deforestation to the ozone hole and acid rain. It is no surprise then that psychedelics and environmental issues have been entangled in the Western imagination—at least speculatively—for some time. Some enthusiasts credit recreational drug use for the entire environmental movement of the 1960s, citing Stewart Brand’s famous LSD trip and subsequent crusade for the first photo of Earth from space. The image catalyzed environmentalists to see the planet as a fragile whole in need of help. Late in life, even the creator of LSD, Albert Hofmann, advocated for the ecological imperative of psychedelics:

“Alienation from nature…is the causative reason for ecological devastation and climate change. Therefore I attribute absolute highest importance to consciousness change. I regard psychedelics as catalysers for this.”

But the hope that tripping will save society was most widely championed by Terence McKenna, a celebrated psychedelic bard known for multi-hour, genre-hopping raps and an at least half-serious theory the world would end in 2012. He speculated that psychedelics—namely tryptamines—offered gateways to the “Gaian mind” of the planet, allowing humans to hear the collective cry of ecosystems in crisis, and offering a way forward.

McKenna proposed a number of solutions to save Earth, ranging from practical (reform toxic waste disposal and restore natural ecosystems) to sweeping (reign in commodity consumerism) and even ecofascist (limit all women to one child); however, he said these changes were impossible without widespread psychedelic drug use. Echoing my philanthropist friend, he urged us to merge with the Gaian mind, then “the plans will come.”

The current psychedelic landscape looks very little like it did when McKenna died in 2000. The current professionalized so-called “Psychedelic Renaissance” deploys high-profile journalistic gatekeepers and reputable scientific institutions to legitimize the medical benefit of psychedelic drugs through rigorous, peer-reviewed research. Visionary speculation has been supplanted by rational extrapolation.

Hiding amidst dry discussions of clinical protocols, p-values, and institutional review boards lurks the same old hope: psychedelic experiences won’t just help individual minds, they will reveal how we can heal the world. Millenarianism got a modern facelift: evangelists now brandish peer-reviewed clinical research instead of trip insights to defend—often tenuously—their broader societal hopes.

One hears echoes of latent, salvific fervor in statements from even the most buttoned-up researchers. In an interview, Johns Hopkins University researcher Dr. Roland Griffiths speculated:

“The core mystical experience is one of the interconnectedness of all people and things, the awareness that we are all in this together. It is precisely the lack of this sense of mutual caretaking that puts our species at risk right now, with climate change and the development of weaponry that can destroy life on the planet.”

While Griffiths goes on to warn that the solution is not that everyone should take psychedelics, others are less cautious.

Sam Gandy, a research collaborator with Imperial College London, most strongly advocates for psychedelics as an environmental solution. As evidence, he marshalls several scientific publications, including a depression study linking psilocybin to increased nature relatedness, and an online survey showing psychedelic users report more pro-environmental behaviors—such as recycling and conserving water—relative to other types of drug users. In a paper titled “From Egoism to Ecoism,” Gandy and his colleagues confirm the connection between psychedelic ego dissolution and nature-relatedness, obliquely insinuating decriminalization is a viable environmental strategy: “It would seem [the] widespread prohibition [of psychedelics] is not in the best interests of our species, or the biosphere at large.”

Gandy has even suggested that psychedelics could play a role in “converting nature skeptics.” Similarly, University of California Davis researcher David Olsen has posited that psychedelics could be used to turn people into activists by introducing climate concepts during their trips. One wonders who among the target demographic would knowingly participate in such an experiment. Nevertheless, it is deeply disturbing to see members of the psychedelic research community gesture towards brainwashing, even with the best of intentions.

The media has run with this logic, publishing headlines that range from wishful (“How Psychedelic Drugs Could Help Save the Planet”) to questioning (“Could psychedelics help resolve the climate crisis?”) and downright reckless (“If Everyone Tripped on Psychedelics, We’d Do More About Climate Change”).

As this scientific refresh of McKenna-style millenarianism takes root in the media, there has never been a more important time to engage it on its own terms.

Let us accept for now the finding that psychedelics may increase nature-relatedness, which in turn might increase pro-environmental behavior. Which behaviors? For how long? Is everyone, everywhere, supposed to take a high-dose, professionally-guided, lab-grade psilocybin trip? If not, who?

An extremely charitable interpretation of the “egoism to ecoism” logic might lead us to conclude that enough individual behavior change would eventually snowball into policy that would solve climate change, producing a kind of psychedelic herd immunity that suddenly greens our collective conscience.

This is a dazzlingly naive appraisal of the political economy of global warming, one that nobody who actually works on movement mobilization believes. Climate change, the single most complex global collective action problem the world has ever faced, will not be solved by psychedelic medication turning us all into diligent recyclers. To assume so is textbook magical thinking.

In fact, some experts argue individual choice is statistically blameless for the climate crisis. For evidence, look no further than the current pandemic. Despite billions of people sheltered in place, global greenhouse gas emissions for 2020 are estimated to drop somewhere between 4 and 7%. For context, to meet our most ambitious global climate change goals, emissions need to drop at least that amount every consecutive year for the next ten years.

Given the untold suffering COVID-19 has wrought, this modest reduction is no cause for celebration. Without meaningful legislation, emissions will likely rebound worse than before the pandemic—such as occurred after the 2008 financial crisis. In fact, as the economy re-opens, global emissions are already surging back. China’s air pollution has skyrocketed to rates higher than before the pandemic. 2020 is slated to be the hottest year on record. The Arctic is on fire. And in May, atmospheric CO2 concentrations reached their highest level ever.

COVID-19 lays bare what climate activists know: our current crisis is not simply the result of our individual behavioral choices, but of an economy structured by vested interests to put profits before planet. Take, for example, that just 100 companies account for 71% of global emissions since 1988. These fossil fuel interests have spent billions of dollars on efforts to mislead the public, sow climate denialism, and secure trillions of dollars in subsidies, stymying efforts to ensure a livable future on Earth. That’s why we don’t just need LSD to repair our relationship with nature; we need sweeping structural change that encodes this relationship by making large polluters pay the price for planetary destruction.

Quarantine may have forcibly increased our connection with nature. But while Americans learn bird calls, celebrate urban wild animal invasions, and plant pandemic gardens, the Trump administration is busy rolling back key environmental wins of the last decade, including nixing fuel economy standards, selling off public lands, and suspending air pollution enforcement. The meat and fossil fuel industries―two of the largest climate culprits―have requested what essentially amount to public bailouts, while the coal industry snagged $31 million in stimulus loans for small businesses.

So if the psychedelic hypothesis asserts that “experiences of interconnectedness are de facto good for the planet,” COVID-19 offers a resounding no.

Proponents of the “egoism to ecoism” logic would be wise to exercise caution for several additional reasons. Firstly, it is worth emphasizing that unitive, mystical-type experiences are by no means a universal phenomenon while tripping.

Moreover, there is no linear path for how experiences of oneness affect ethics, politics, and actions. Conflating these categories creates a dangerous moral hazard I call psychedelic antinomianism, whereby one substitutes a mystical experience for a moral education. The risk is that psychonauts absolve themselves of the responsibility to educate, mobilize, and act on climate change. After all, when you “get to oneness, the rest will work itself out.”

As religious scholar Jeffrey Kripal has argued, there is no necessary or simple connection between the mystical and the ethical. The world is too rife with counterfactuals to believe so: toxic gurus, sexual abuse by psychedelic leaders, not to mention the inconvenient truth of psychedelic use among alt-right and white supremacist groups. One does not come out of a psychedelic trip knowing right from wrong, let alone if a carbon tax is preferable to a cap-and-trade system.

While an experience of oneness might motivate some to care for the collective, others could double down on self-interest. The fragile reciprocity of Earth is exactly why Jeff Bezos is spending billions to abandon it, and why millionaires are building luxury climate change bunkers and paying private security firms to protect them when the rest of us succumb to utter climate chaos. Even psychedelic evangelist Timothy Leary ridiculed the ecology movement, calling the field “a seductive dinosaur science.” Why bother with Earth when humankind, he maintained, would soon migrate into space?

For those with privilege, interconnectedness is a risk to be managed, not a precious insight from which to build a better world for all.

An unfortunate feature of the “egoism to ecoism” discourse is its unintentional spiritual elitism, which frames unitive consciousness as the most enlightened grounds for environmentalism. But feeling one with nature is neither the only nor the best reason to care about the future of our planet. There are numerous, equally valid motivations for environmental action: indebtedness to future and previous generations, justice, or rage. The most effective and vocal environmental leaders today—from Greta Thunberg to Xiuhtezcatl Martinez to Michael Mann to Varshini Prakash—speak to all of these.

The climate community is no stranger to magical thinking. Every few years heralds a new deus ex machina that aims to undo decades of inaction: injecting particles into the atmosphere to block out the sun, building big boxes that suck carbon from the air, fertilizing the ocean. Psychedelics.

I do not dismiss that psychedelics can catalyze profound personal healing and meaning-making; I know from firsthand experience they can. Individuals should have access to these medicines in safe containers, with adequate preparation and support for integration. And I do not wish to disparage what is effectively the oldest and most global form of religious experience and expression, namely, so-called magic. But I walk a delicate line: a mystic who writes policy memos, a climate wonk who accepts the Keeling Curve as much as I do non-rational ways of knowing. Imagining the future falls equally on shamans and priests and soothsayers as on scientists and political organizers, and I appreciate the disparate modes through which their respective visions take shape.

But when it comes to climate change, the future is already here, and it is bleak. We have no time to mistake magical thinking for a viable political strategy. Psychedelic trips, while they may be meaningful starting points for individual change, are dangerous endpoints for societal change. A high carbon footprint is not a pathology to be treated in a lab or healed in an ayahuasca ceremony; it is a design feature of our petro-capitalist culture.

I believe that magical climate thinking arises due to profound, unexpressed emotional pain: guilt and grief. (Coincidentally, I suspect psychedelics are uniquely well-suited to help climate activists and scientists process climate grief and avoid burnout.) As we kill coral reefs and extinguish billions of birds, as extreme weather and zoonotic illnesses threaten life on Earth, we do not just mourn what is lost, we also continually confront our responsibility for that loss.

The pain is almost too great. As a result, theological ethicist Jacob Erickson writes, “one might hopefully feel, perhaps, that current actions attending to one crisis could magically undo the harms done in another.” Maybe all the great research on psychedelic drug trials will contain the key to greening society, we pray. Maybe quarantine will finally cool our scorching world.

But the pandemic has taught us a painful lesson: magical thinking can be lethal. “[COVID is] going to disappear. One day it’s like a miracle—it will disappear.” Treatments must be appropriate to what ails us. Upholding psychedelic drugs as a viable emissions mitigation strategy is as thoughtless as promoting hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19. Claiming drug-occasioned oneness will save the planet is the tone-deaf moral equivalent of celebrities singing “Imagine” on social media.

Peak experiences do not prescribe politics. Ego-dissolution is great, but one needs an ego to vote, blockade, or otherwise resist the destructive realities of our time. And I believe the single most important climate action this year is electing candidates at all levels of government who support bold legislation to price carbon, incentivize clean energy, protect natural ecosystems, and ensure a just transition—all while recovering from the economic devastation of the pandemic.

The psychedelic community owes the world something more constructive than “tune in, turn on, save Earth.” If psychedelic activists and researchers truly care about societal change, they must stop peddling crypto-libertarian narratives that privilege freewheeling individual experience over the need for collective organizing and sweeping, structural reform. They should mobilize their communities to support clear policy agendas like the Green New Deal, our best chance right now to tackle climate change at the requisite speed and scale. Notably, some plant medicine activists, such as Dr. Bronner’s and Gail Bradbrook of Extinction Rebellion, are doing just this.

If the psychedelic community really wants to shift consciousness for good, it might even lobby for programs that get students into nature, or mandatory national climate change curriculum, like those recently introduced in schools across New Zealand and Italy. These interventions scale, have no risk of a bad trip, and unlike psilocybin or LSD, have been demonstrated to cost-effectively reduce emissions.

Neither psychedelic- nor viral-occasioned oneness will “solve” climate change. Because when the trip ends, the hard work begins. Dosing people is cheap and easy relative to changing the material conditions that enable their exploitation, or helping them meaningfully interpret experiences and marshall insights into a life worth living. Integration is slow, costly, and difficult—much like the political mobilization that Doblin insinuates has failed climate change over the decades. But episodes of watershed societal change, from women’s suffrage to equal rights to gay marriage, did not magically happen overnight. They required years of sustained political pressure, innovative alliances, and a suite of creative, complementary tactics.

Simply put, they required a plan.

Worldwide, nations are deliberating how to spend trillions of dollars of pandemic stimulus funding, a once-in-a-generation spending opportunity to “build society back better.” Will these funds go towards more coal plants, congested cities, and corporations that ravage our natural resources? Will they propagate a broken healthcare system? Or will they build more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable societies? How will society integrate this trip?

To answer these questions, we need more than unity with nature. We need a unified political agenda to dismantle capitalist logics that prioritize profit above people and planet. Because as Terence McKenna also famously said, “If you don’t have a plan, you become part of somebody else’s plan.”

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Rachael Petersen

Rachael is a writer and environmental consultant who advises nonprofits and foundations on climate change. With an expertise in tropical forests, Rachael has conducted fieldwork in the Brazilian and Ecuadorian Amazon, Borneo, Uganda and elsewhere. After almost a decade in climate policy, Rachael has turned her attention to the spiritual implications of our current ecological crises. Rachael stumbled into psychedelics as a participant in a psilocybin clinical trial for major depression. Her writing excavates the potential risks, rewards, and societal implications of medicalizing and commercializing mysticism. Her work interrogates the intersection of the mystical and the moral, and envisions the role of non-ordinary states of consciousness in current and future forms of religion. Rachael explores these themes as a Junior Fellow at Harvard University's Center for the Study of World Religions.