Coming Out of the Psychedelic Closet

Who am I? How do you answer that question? I’m a mother, a wife, a teacher, a scholar. And I’m also a psychedelic woman.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Presented at Psymposia: Envisioning a Post Prohibition World. University of Massachusetts Amherst, April 18, 2015. Read the Coming Out of the Psychedelic Closet conversation.

The question of identity arises from the psychedelic experience itself: Who am I? How do you answer that question? I’m a mother, a wife, a teacher, a scholar. And I’m also a psychedelic woman. I first heard the phrase “psychedelic woman” during a talk by Annie Oak at the Horizons psychedelics conference. It resonated with me, and I started to think more about the intersection of psychedelics and identity.This presentation is the result of five years of thinking deeply about the parallels between psychedelic identity and the LGBT rights movement.During this talk, I’ll address three main questions:

- First, What does it mean to identify as psychedelic?

- Next, What parallels can be drawn with the LGBT rights movement?

- What does it mean to “come out” as psychedelic?

So first, what does it mean to be a psychedelic person?Sasha Shulgin writes in the beginning of PiHKAL that “For many thousands of years, in every known culture, there has been some percentage of the population…which has used this or that plant to achieve a transformation in its state of consciousness.”Going back even further, the recent discovery of a 100-million-year-old psychoactive fungus supports Mike Jay’s argument that “we’ve been taking drugs longer than we’ve been human.” The intense stigmatization and criminalization of psychedelics is a recent phenomenon.But I want to return to Shulgin’s phrase, “some percentage of the population.” There are some people for whom psychedelics are more than just a fun time on the weekend.

Take Ann Shulgin’s description of her first mescaline experience, also from PiHKAL:

“The funny thing is that, despite all the newness, there’s something about all of it that feels–well, the only way I can put it is that it’s like coming home. As if there’s some part of me that already knows—knows this territory,—and it’s saying Oh yes, of course! Almost a kind of remembering–!” – Ann Shulgin, PiHKAL p. 120

My friend Becky semi-jokingly compared this experience to receiving a letter from Hogwarts. You go about your life thinking you’re a Muggle, and all of a sudden you discover a part of yourself that actually existed all along.

But not everyone has this kind of a reaction to psychedelics, and that’s okay. And just like someone can be gay without ever having sex, I believe that some people are psychedelic without ever taking drugs.

But I discovered that this comparison of queer and psychedelic identities is controversial after I first published some thoughts about it in a 2010 Reality Sandwich article.

Reactions were extremely polarized. Some people wrote to tell me how much the comparison resonated with their own truth and their struggles. But other people were deeply offended, and felt that the appropriation of LGBT discourse trivialized LGBT struggles.

I am certainly not suggesting that the oppression of psychedelic people is identical to the oppression of LGBT people. But the continuing struggle of one oppressed group is not sufficient reason to avoid discussions about other kinds of systemic oppression.

Which raises the question: are psychedelic people actually oppressed?

It’s an injustice that people like Timothy Tyler are serving life sentences—without the possibility of parole—for the nonviolent charge of “conspiracy to possess LSD with intent to distribute.” Many murderers and rapists get less time than that. Tyler considered LSD to be a sacrament. He’s a Grateful Dead follower who was locked away in a federal prison where, for two decades, listening to music was forbidden.

Another Deadhead was Rudd Walker, who died in prison this past December after serving over a decade of a life sentence.

People who choose to take psychedelics run the risk of losing their jobs, being disowned by their families, and losing their children to state custody. Those are very real and very troubling consequences.

So yes, I think this discussion is important.

I also think it’s important to address the criticisms against it.

So on the basis of this reasoning, the gay rights movement is allowed to draw on civil rights discourse, but psychonauts aren’t allowed to draw on gay rights discourse.

This person positioned herself as an authority on this subject, as an LGBT activist who has tripped and been to Burning Man. She had witnessed firsthand how nonessential psychedelics are, and I believe that’s true for her. But I don’t believe she’s in a position to speak for all psychonauts.

To consider a different angle on her reasoning, here’s an alternative scenario: What if I’ve been involved with multiple women during my life, but I don’t identify as a lesbian? If someone told me that I couldn’t be with another woman ever again, it wouldn’t be a deal to me. But does that give me the right to tell a lesbian that, therefore, it shouldn’t be a big deal to her?

My psychedelic identity is personally a bigger part of my life than my gender identity or sexual identity.

Consider for a moment the LGBTQIA acronym. It ends with the letter “A,” which stands for both “Ally” and “Asexual.” An asexual person is someone for whom, by definition, sexuality is not the most important aspect of their identity. So even within this acronym, there is an arrow that points to identities beyond it.

While we’re here, let’s also consider the letter “T,” which stands for “Transgender.” The transgender movement has taught us that we need to believe people when they say who they are. If I say I am a psychedelic woman, who has the right to tell me that my experience of myself is false?

In the process of thinking through these ideas, I decided to look more deeply into the history of the gay rights movement and its reliance on civil rights discourse. Something surprised me: the gay rights movement had to defend itself from criticisms that were essentially identical to the criticisms being directed against psychonauts, today.

For instance, some people say psychonauts don’t have a right to claim that they’re an oppressed group. Psychonauts are mostly privileged, wealthy white people who just want an excuse to have hedonistic parties, right?

Compare this to legislation debates about gay rights from the early 1990s, as described by Michael Bronski in his book, The Pleasure Principle:

Bronski describes the view that “Gay men and lesbians did not need ‘special rights’ because, far from being disenfranchised, they already were wealthier, had better jobs, more leisure time, and more disposable income than almost any other group in the U.S. economy. … For many in the mainstream, the ‘privileged economic status’ of homosexuals was conflated with their already established view of gay people as pleasure seekers and sexual libertines.”

Being gay was seen by many as a deviant lifestyle choice. But gay people weren’t convinced by this argument.

Michael Nava and Robert Dawidoff set out a defense of the alliance between gay rights and civil rights in their book Created Equal: Why Gay Rights Matter to America. For our purposes here, I swapped out the authors’ original race and sexuality terms for my own sexuality and psychedelic terms. The argument is still valid with these changes.

Take for instance, this altered quote:

“The special character of [sexuality] within this society and of the [gay] rights movement that grew out of it cannot preempt other movements for civil rights…. [Some members of LGBT communities] are understandably sensitive and protective about the routine appropriation of their particular historical experience and the particularity of the extraordinary movement they carried forward to challenge their oppression. Nevertheless, the movement’s claim…was to a common set of principles that must apply to everyone…. If women, racially and ethnically diverse groups, [LGBT people] and now [psychonauts] rush to the standard first carried by the African-American civil rights movement [and subsequently by the LGBT movement], that is not stealing but believing. Those who are so quick to denounce the appropriation of civil rights by movements based in gender, sexual orientation, physical ability, and [other modes of identification] probably need to examine their own record with respect to human differences other than race [or sexuality].”

The authors suggest that the key contribution of the gay rights movement to the history of civil rights and civil liberties is its re-emphasis on the individual—an “individual asserting personal rights to personal freedom for personal choice about the personal life.”

They continue, “The labeling of gays as…degenerate and unnatural is the same kind of labeling that has always been used to justify the denial of rights to individuals belonging to ‘minority’ communities.”

Remixing the authors again: People who are quick to shoot down the possibility of a psychedelic identity “deny the validity of personal experience when it is at odds with convention. … In effect, [psychedelic] men and women are taught that their experience of themselves as decent, productive, loving humans is false, because [drug use] is unnatural and sinful.”

In the face of this, the “act [of coming out] is the acceptance of one’s fundamental worth…in the face of social condemnation and likely persecution.”

But it is common for members of oppressed groups to resist alliances with other groups.

Andrew Solomon describes this phenomenon in his book Far from the Tree, where he explores what he calls “horizontal” identity categories–identities that people don’t necessarily inherit from their parents.

He writes that: “Deaf people didn’t want to be compared to people with schizophrenia; some parents of schizophrenics were creeped out by dwarfs; criminals couldn’t abide the idea that they had anything in common with transgender people…and some children of rape felt that their emotional struggle was trivialized when they were compared to gay activists. … The compulsion to build such hierarchies persists even among these people, all of whom have been harmed by [such hierarchies].”

But Solomon cites the theory of “intersectionality” as an alternative to this trend.

“Intersectionality is the theory that various kinds of oppression feed one another—that you cannot, for example, eliminate sexism without addressing racism.”

Solomon quotes Benjamin Jealous, president of the NAACP, who said: “If we tolerate prejudice toward any group, we tolerate it toward all groups. … We are all in one fight, and our freedom is all the same freedom.”

I argue that it doesn’t serve us to cherry pick which identity groups are worth protecting and which are not. We need to focus on a common set of core principles, and honor the right of individuals to make decisions about their own minds and bodies.

Which brings me to the final section of my presentation. What does it mean to “come out” as psychedelic?

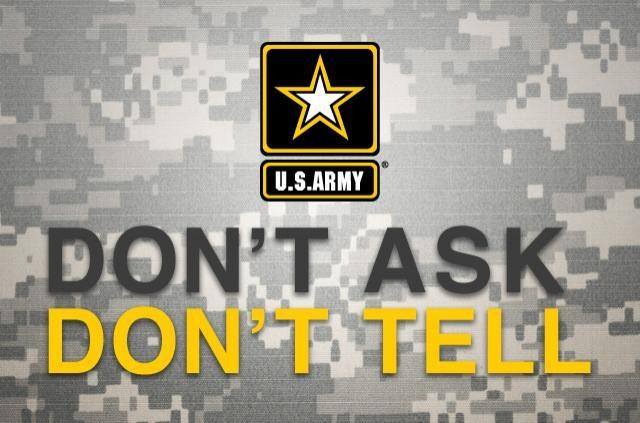

I’ll start with my own case: When I went to college, I didn’t understand why the military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy was such a big deal. Why did people need to talk about their sexuality at work? But then I moved from Bard College—a hippy school in the woods—to the University of Pennsylvania for graduate school. Suddenly I didn’t know anyone who’d had meaningful psychedelic experiences. I felt that I needed to keep that part of me hidden, and it was an extremely lonely time. I learned then the hard way that hiding part of who you are can have a deep psychological impact.

“Coming out” as psychedelic was profoundly liberating. Instead of studying Romantic poetry “because of” my secret interest in psychedelics, I started researching poetry explicitly “alongside” psychedelics. In my case, this doesn’t mean that I continue to use psychedelics today. As a mother and teacher, the current political climate makes the risks outweigh the benefits. But psychedelics helped me work through crippling social anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder during my first year of college, and they shaped my entire worldview and life’s path. This isn’t something I will easily forget.

But “coming out” as psychedelic entails a whole spectrum of possibilities. It can mean describing past use, but it can also mean striking up a conversation about the latest research out of NYU or Johns Hopkins. It can mean forwarding a recent article in the New Yorker or New York Times to your mom or your boss or your colleague, or even planning a trip to drink ayahuasca in a country where it’s legal.

Taking a different tack, you can also choose to be a psychedelic ally, rejecting the current state of the drug war while personally abstaining from psychedelic use.

What’s important here is that people are mindful of the decisions they’re making and why. Sometimes it can be more strategic to keep things under wraps. If you teach children or require a security clearance to work for the government, for example, it might make sense to hold some of your interests and experiences back.

But if you’re holding back on “coming out” because of a knee-jerk fear reaction, I encourage you to reconsider. Sometimes the risks are low, and sometimes the risks are worth taking.

The abolition of sodomy laws in this country did not eradicate homophobia, and anti-psychedelic prejudices will still exist in a post-prohibition world. By banding together, we have the power to own our narratives and to shift the cultural dialogue.

And as people have noted at this event, it’s important to create safe spaces where people can come together to share their ideas and experiences without fear of persecution. Many cities host regular psychedelic discussion groups. In Philadelphia, we have Theorizing Psychedelics, which meets biweekly. San Francisco has the San Francisco Psychedelic Society. And Baltimore has its Psychedelic Seminars, just to mention a few. I encourage everyone here to either get involved with their local groups or create a new group for people to come together on a regular basis.

Terence McKenna argued that sovereignty over one’s consciousness is the next great civil rights struggle after sexism, racism, and homophobia. “Coming out” about one’s psychedelic identity, interests, and/or experiences is an important part of redefining the public perception of psychedelics and of those who choose to experience their effects.

But this debate is ultimately much bigger than us. In the words of Nelson Mandela: “For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

At the end of the day, despite all differences, everyone deserves our compassion and respect.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Neşe Devenot

Neşe Devenot is the Medicine, Society and Culture Postdoctoral Scholar in Bioethics at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. Previously, she was a founder of the Psychedemia interdisciplinary psychedelics conference, a Research Fellow at the New York Public Library’s Timothy Leary Papers, and a Research Fellow with the New York University Psilocybin Cancer Anxiety Study. She was awarded Best Humanities Publication in Psychedelic Studies from Breaking Convention and received a Women of the Psychedelic Renaissance grant from Cosmic Sister. Her research explores the function of metaphor and other creative uses of language in descriptions of psychedelic experiences, as well as abuses of power and hegemonic social forces within the psychedelic community.